UPDATE: Sometimes you just screw up. When I was writing this post, I really wanted to talk about Strasburg’s retirement and tie it into recent thoughts I’d had on the subject. But I’d also just finished reading The Tao of the Backup Catcher, and since it was about baseball (in a way) I thought I’d just tie the two together. Bad decision. In doing so, I missed the lede on this gem of a book and gave it short shrift. It is really a remarkable tale of servant leadership, a topic I’ve covered before, most fully here. So if you choose to read the book (and I hope you do) remember that it is much more about servant leadership than handling retirement gracefully. As they say, sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, and sometimes it rains. This post as originally written was somewhere in those latter two categories.

The announcement of Stephen Strasburg‘s retirement from baseball was delayed, a fiasco only the Washington Nationals could pull off. Nonetheless, the news has me thinking about the timing, difficulty, joy, and fragility of retirement. All of it.

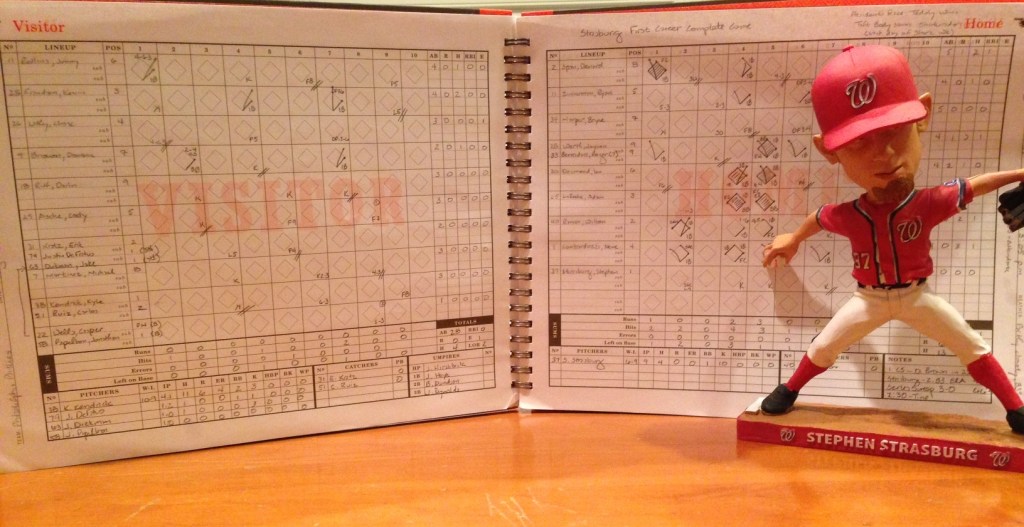

Strasburg, who spent his entire career with the Nationals and won a World Series MVP award in 2019, was “perhaps the most thrilling pitching prospect in baseball history.” His 2010 debut was electric, a “seminal moment in the arc of baseball in Washington.”

The last-place Nats sold out Nationals Park for what was billed as “Strasmas.” A Tuesday night against the lowly Pittsburgh Pirates became a marquee event, with MLB Network broadcasting the game nationally.

Strasburg delivered. Before that night, no pitcher had struck out as many as 14 hitters without walking any in his big league debut. That’s what Strasburg did against Pittsburgh in a 5-2 victory for the Nationals.

During a stellar yet injury-prone career, Strasburg was a three-time All-Star with a 113-62 record. He became the fastest pitcher by innings to strike out 1,500 when he reached the mark in 2019. The stoic Strasburg even started to smile that year.

My hope is that this famously earnest athlete can now find the time and head space to bash into even more joy in the years ahead.

Expressing joy wasn’t a problem for Willie Mays. As I’ve written earlier, the only thing Mays couldn’t do on a baseball field was stay young forever. And therein lies the nub of our human condition. We’re all mortal.

Just as Mays discovered his mortality the hard way, Strasburg retired at age 35 because, “even after removing a rib and two neck muscles,” Joe Posnanski writes, “the doctors couldn’t quite put his body back together this time (as they had so many times before).”

Strasburg and Mays were elite athletes who, when healthy, were at the top of their profession. In other words, very different from 99% of us. And even very different from other teammates. Like the backup catcher.

The Tao of the Backup Catcher: Playing Baseball for the Love of the Game (2023) by Tim Brown and Erik Kratz is “a story about a part of the game that hasn’t drifted into a math contest.” A catcher at Eastern Mennonite University who holds the Division III record for doubles, Kratz is discovered by a scout who sees something that suggests he has what it takes to get to the majors. Perhaps not to be a star, but to be the guy who is always there when the star catcher needs a day off from bending down behind home plate, catching 100-mph missiles, and taking foul balls off the left kneecap.

Backup catchers hang on, even if they must play for a variety of teams. When they are really good at what they do they can make a baseball career out of it. They watch and listen and ponder.

There’s a reason why, among other virtues, they caught twenty-three of the sixty-nine no-hitters thrown in the twenty-first century, and before that, why they’d caught six of Nolan Ryan’s seven no-hitters.

The values and competencies of backup catchers are often undefined. They ask: What can I do to help? Perhaps the answer “comes less from an understanding of how the game works and more from a deep familiarity with — and appreciation for — how oneself works.”

It’s not about letting go of your dream “but letting go of the ego.”

Brown begins this gem of a book at Kratz’s retirement. Unlike many backup catchers who are simply let go, Kratz leaves on his own terms.

He wouldn’t again be overlooked, optioned out, sent down, released, traded, waived, designated for assignment, nontendered, benched, ignored, hidden on a disabled list, lied to, pinch-hit for, or promised better.

That step, minus the baseball jargon, is more in tune with how so many leave their professions and move into retirement. No tribute videos before adoring crowds, no future Hall of Fame speeches. If we’re fortunate, the locker room attendants or the IT staff have nice things to say about the way we’ve worked to uphold our part of the team, treated others with kindness, and moved the organization forward.

And it is very hard to know when to let go. A friend told me the story of a colleague who said,

One should retire 1) while you are still enjoying the job and believe you are working at full capacity, 2) before people start wondering why you persist in hanging on, and 3) so that a younger person can have their turn.

I generally agree; however, those suggestions don’t always work. Being in the group of the formerly young, I recognize and appreciate the value of experience. The inequities in our safety net mean some have not had the opportunity to build for a comfortable retirement. My former colleague Nick Kalogeresis wrote an insightful piece about the decline of his beloved Greektown in Chicago due, in part, to retiring business owners who never found a son, daughter, or relative willing to take on running a new restaurant.

As in the rest of life, there is no one-size-fits-all answer.

But we often know instinctively when someone should retire. Several people in my circle of life stayed in their jobs too long because ego got in the way. Who they were was literally wrapped up in their job. The more we can set aside our ego, the more we can live life as it is meant to be lived.

I wanted to nourish my soul in retirement while I was still, as Mirabai Starr says, “thirsty for wonder.” To learn how I might live even more in peace with life’s uncontrollability. “We won’t last forever,” Natalie Goldberg writes. “Wake up. Don’t waste your life.”

Letting go can involve disappearance along with a sense of transience and fragility. Disappearance, Kathryn Schulz suggests, reminds us to notice, transience to cherish, fragility to defend. “We are here to keep watch, not to keep.”

With eternity always at your door, live all your life — whether star or backup catcher — in full bloom with a thirst for wonder.

More to come …

DJB

Image: Keith Johnston / Pixabay

Pingback: Observations from . . . September 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The books I read in September 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Opening Day . . . 2024 | MORE TO COME...