Remembrance has a powerful pull on our psyches. We all want to leave a legacy and something to show that we existed, for a short while, on this planet. We may do that in many ways, but the task is more difficult — and perhaps more urgent — when a key part of your identity is being erased before your eyes.

When extinction is happening in real time.

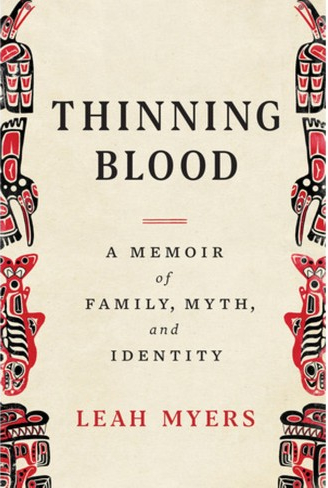

Thinning Blood: A Memoir of Family, Myth, and Identity (2023) by Leah Myers is one young Native American’s powerful push against that feeling of extinction. This is a fierce piece of personal history by Myers, who may be the last member of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe in her family line due to her tribe’s strict blood quantum laws. She is searching for ways to ensure that her identity, her family’s story, and the tribe’s history in the Pacific Northwest’s Olympic Peninsula is not lost forever.

While I am not drawn to memoirs by writers of such a young age as a matter of course, there was a compelling nature to this meditation by the not-yet-30-years-old Myers that called to me. Hers is a young Native American voice from a child of the 21st century raised between Native and white worlds, fearful that her culture is being “bleached out.” She is searching for a personal as well as a tribal identity. Myers speaks honestly about how some Native Americans lump her family among those who “are only Indians when they have their hands out for something.” And how many of her white friends just assumed she was white, given the lightness of her skin. She never grew up on a reservation and had been removed from her culture. She often felt she didn’t belong. Yet she is writing to stake her claim as “Native enough” to tell these stories and take her place alongside the ancestors.

In Thinning Blood, Myers brings together family remembrances, folk tales, tribal history, Native mythology, and her individual story to craft a narrative both personal and communal. She draws on the character of the women in her line — her great-grandmother’s strength, her grandmother’s determination, her mother’s compassion — to shape her voice and story. Noting that totem poles are used to represent stories or places, the totem pole she crafts in her mind and that provides the shape for this memoir represents her family. And the symbols each family member takes — bear, salmon, hummingbird — corresponds to their character and what they’ve passed along to her — the raven — who is given voice and has a story to tell.

There are several powerful sections that deserve special attention: Myers rewatching her favorite childhood movie, Pocahontas, to focus on the hurtful stereotypes that permeate Disney’s storytelling; her struggling with the Klallam language as a young adult; and, most disturbingly, the brutal violence against her body by a teenage white “friend” that almost killed her. The chapter An Annotated Guide to Anti-Native Slurs could stand alone as a useful and educational read for all non-Natives.

Myers also addresses a very current issue in her memoir: genocide and Native adoptions. Genocide is defined as the deliberate and systematic destruction of a racial, political, or cultural group. The United States government has a long, dark, and still largely unacknowledged history of attempted genocide against Native Americans. In recent years, Myers notes, what was once an effort of blunt force became more subtle as the government “carved apart families and the women who could create them.”

After a brutal past of stealing children from their mother’s arms to send them to boarding schools to “kill the Indian and save the man,” The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 sought to keep Native children in tribal communities. The New York Times had a thoughtful story in May about this brutal history, its impacts on those who were taken from their communities, and how our radical Supreme Court — intent on returning America to some fictionalized version of the past — may overturn it. *

Thinning Blood closes with Myers writing a letter to her seventh-generation descendent — someone she never expects to exist due to her decision not to have children — and with a sobering explanation of what will happen to her homeland, the Olympic Peninsula, when the “really big one” comes and the earth is swallowed up by the sea. In this moving and honest outreach to a child who will never be and her clear-eyed assessment of the fragility of life, Myers brings her journey through her family’s history and her search for identity to a fitting close.

More to come…

DJB

*UPDATE: Late on Tuesday evening, June 14th, the Supreme Court by a 7-2 vote, upheld the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which gives preference in the foster care and adoption of Native American children by their relatives and tribes. This is a big win for Native Americans.

The Weekly Reader links to the works of other writers I’ve enjoyed. I hope you find something that makes you laugh, think, or cry.

Photo by Benjaminrobyn Jespersen on Unsplash

Pingback: Observations from . . . June 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The books I read in June 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2023 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...