How often have you heard that America is exceptional? Would it surprise you to know that citizens of other countries also hear that their homeland possesses desirable qualities that others lack? French nationalists “tout the elegance and sophistication of their ‘civilization.'” Serbians “have traditionally considered themselves the shield of Christianity.” Haitians take pride in being “the first country whose people freed themselves from slavery.”

Protestants coming to America in the 1600s imagined themselves as creating a new Israel. But early colonists imagined themselves as Romans “at least as often as they saw themselves as Israelites.” The people of an “endless frontier” became popular in the nineteenth century. Madeleine Albright called the U.S. “the indispensable nation” in guaranteeing global security.

Historians don’t find much about British and Japanese exceptionalism in the literature, but that “may derive simply from the fact that scholars of both countries take the exceptional status of each so utterly for granted.”

The idea of “American exceptionalism,” in other words, falls squarely into an entirely common pattern. There is nothing exceptional about it.

American exceptionalism, like so many other myths, has warped our ability to understand the past in a constructive way. In today’s age of disinformation, the line between fact and fiction has become “increasingly blurred if not completely erased.”

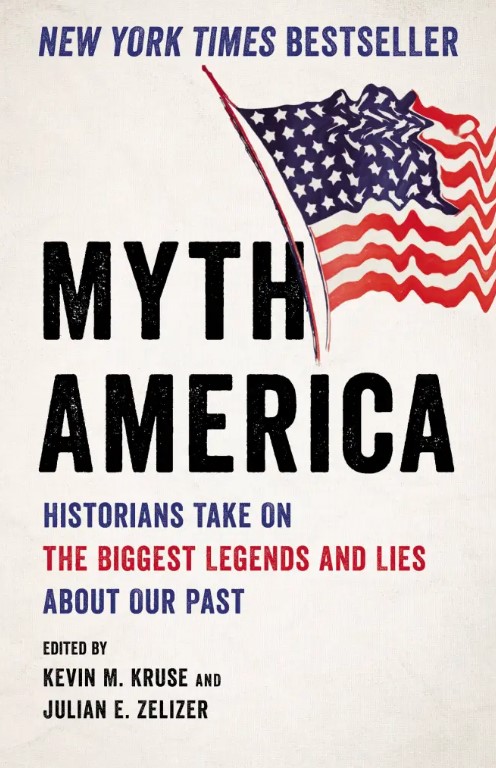

Myth America: Historians take on the biggest legends and lies about our past (2022) — edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer — tackles many of the most dangerous myths about our nation’s past. There have always been lies in our public discourse but in the introduction the editors assert that “in the last few years the floodgates have opened wide.” They cite the political campaigns and presidency of Donald Trump, the creation of the conservative media ecosystem, and the “devolution of the Republican Party’s commitment to truth” as the major causes. Yet as many of these top historians demonstrate in a series of illuminating essays, the war against truth in America has been fought over a much longer timeframe.

Claims about what happened in the past can be “misleading and even malignant.” Unfortunately for the country, the results can cause long and deep damage. Karen L. Cox writes that the evolution of the more than 150-year-old “Lost Cause” falsehood “offers proof that it was never tied to a factual history but was always about an alternate reality.”

Historians are influenced by their context and will sometimes disagree. “It is quite another thing to ignore the facts altogether.”

The historians take on myths including those around vanishing Indians, immigration, the border, family values, the impact of the New Deal, and voter fraud. Because there has been such a robust debate over “the role of slavery in America’s political development” especially out of the 1619 project, the editors turned their focus elsewhere.

While the twenty essays are not uniform in quality, all are insightful and enlightening. Several tackle myths that burrow deep into our subconscious.

- Yale’s Akhil Reed Amar takes on the widely held belief that James Madison was the “father of the Constitution.” He argues that “The Convention that ensued (at Philadelphia) was Washington’s convention, not Madison’s; likewise, the proposed Constitution that emerged was emphatically Washington’s,” knocking down four other myths in the process, including the old chestnut that “a republic is not a democracy.”

- Daniel Immerwahr breaks down the enduring myth that America is not an empire-building nation. Empires, of course, have territories. And as early as 1791, 45 percent of our land was composed of territories. Oklahoma (i.e., Indian Territory) was a U.S. territory for more than 100 years, longer than the French held Indochina or the Belgians held the Congo. Today we have five overseas territories, over 500 tribal nations within our boarders, hundreds of foreign bases, and the world’s largest military. Understanding that, it becomes hard to agree with those who put forward the myth that there is nothing imperial about our country.

- Glenda Gilmore — the Peter V. & C. Vann Woodward Professor Emeritus of History at Yale — takes on another deeply held belief: while the right to protest is enshrined in the First Amendment, only a “good protest” is legal and effective. Based on the “passive resistance” of the civil rights movement that began with the Montgomery bus boycott and continued until Martin Luther King’s assassination, it suggests that if current-day supporters of issues such as Black Lives Matters do not conform to this myth of orderly marches in the face of violence, then they aren’t engaged in “good” protests. That false narrative rests on four misconceptions: “that the demonstrations from 1955 to 1968 were the first of their kind, that most Americans gave their support to the protests and their leaders, that they quickly exposed and vanquished hatred, and that they ended happily by bringing racial equality to America.” None of those are remotely true.

- In considering the mythology around white backlashes, Lawrence Glickman notes that blaming the victims of racial discrimination for the “inevitable” response tracks a largely continuous thread across US history that ignores agency, responsibility, and causation. Backlashes are long-term political projects that should be seen as “counterrevolutions” to progress.

- Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway join to take down the myth of the unfettered marketplace as better governance. Millions of Americans believe the best way to solve problems is to leave them to the workings of the marketplace thanks to a decades-long effort led by business leaders in the 1930s to undermine government regulation and support unfettered capitalism. They argued that any compromises to business freedom threatened the fabric of American life. That’s not remotely true either.

These and other essays in Myth America encourage Americans to “see the past closely in order to understand where we stand now and where we might go in the future.” It is a helpful guide.

More to come …

DJB

Other myth-busting books on More to Come:

- How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr

- One Person, No Vote by Carol Anderson

- How the South Won the Civil War by Heather Cox Richardson

- Why the New Deal Matters by Eric Rauchway

- One Nation Under God by Kevin M. Kruse

- Democracy in Chains by Nancy MacLean

The Weekly Reader links to the works of other writers I’ve enjoyed.

Photo from Pixabay

Pingback: Observations from . . . August 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The books I read in August 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2023 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...