If we are honest with ourselves, we will admit that our memories are fragile. The poet Marie Howe has written that “memory is a poet, not a historian.” Yet we often rely on the memory of witnesses in histories, in courts of law, and in our personal lives. Memories fade with time and they change as others share the story of the same event. Points get lost, or found, in translation.

What happens when one of the most transformative events in human history, the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth at the hands of the Roman Empire sometime around the third decade of the Common Era, has to rely on witnesses for transmission across centuries?

Witness at the Cross: A Beginner’s Guide to Holy Friday (2021) by Amy-Jill Levine examines the stories, texts, social contexts, religious background, and perspectives of those who watched Jesus die: Mary his mother; the Beloved Disciple from the Gospel of John; Mary Magdalene and the other women from Galilee; the two men, usually identified as thieves, crucified with Jesus; the centurion and the soldiers; Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus. Dr. Levine, known as AJ to friends, brings her deep understanding of scripture, insightful commentary, broadness of perspective, and engaging wit to help us consider this climatic moment in the Christian story. The Rabbi Stanley M. Kessler Distinguished Professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies at Hartford International University for Religion and Peace, AJ is also University Professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies Emerita, Mary Jane Werthan Professor of Jewish Studies Emerita, and Professor of New Testament Studies Emerita at Vanderbilt University, an internationally known author and speaker, and the first Jew to teach New Testament at Rome’s Pontifical Biblical Institute. She acknowledges the fragility of the memory of witnesses and suggests that readers “do well to listen to their stories and see how their stories transform us. At that point we pick up the stories ourselves.”

In this latest edition of my author interviews on More to Come, AJ graciously agreed to chat with me about her work.

DJB: AJ what led you, as a young scholar, to study the New Testament?

AJL: Stories about the divine have always interested me. This is probably why I liked Hebrew school (at Tifereth Israel Synagogue in New Bedford Massachusetts). My parents told me that Jews and Christians read the same books, such as Genesis and Isaiah; said the same prayers, especially the Psalms; worshiped the same G-d, who created the heavens and the earth, and that a Jewish man named Jesus and a Jewish woman named Mary, were very important to Christians.

When I was seven, a girl on the school bus accused me of killing her Lord. The Vatican II document Nostra Aetate (Latin: “In our Time”), promulgated in 1965, formally ended at least in Roman Catholicism the claim that all Jews are responsible for the death of Jesus. But this incident came before Nostre Aetate.

Not understanding why Christians, given the same G-d and the same prayers, let alone Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, were saying such horrible things, I determined to go to catechism, Catholic education classes, to stop this hateful teaching (I thought it was a translation error, since in Hebrew School we learned Hebrew; nobody told me the New Testament was written in Greek). My very wise mother said something to the effect of, “As long as you remember who you are, go and learn something. It’s good to know about other people’s religions.”

When I read the New Testament, two things occurred to me. First, we choose how we read. Reading this book can incite antisemitism, but it need not. I wanted to learn what the switch was to help people read with compassion, not bigotry. Second, I realized that the New Testament records Jewish history. The first person in literature called “rabbi” is Jesus; the only Pharisee from whom we have writings is Paul.

I decided to study the New Testament. I also promised my mother that if I couldn’t get into a Ph.D. program, get a job, or earn tenure, I’d go to law school. I’m now 67 — law school is no longer an option.

The four gospel writers bring different perspectives and perhaps agendas to the story of the crucifixion. How would you briefly describe what each brings to the story and why it is important to consider them together?

Jesus’s story, like creation (contrast Genesis 1 with Genesis 2-3) or the history of ancient Israel (contrast 1-2 Samuel and 1-2 Kings with 1-2 Chronicles), is too grand for a single version. Matthew’s Jesus is a new Moses, who escapes murder as an infant and who interprets Torah, originally given on Mt. Sinai, in the Sermon on the Mount. At Jesus’s death, the earth shakes, rocks are split, and tombs open: the women at his tomb are the first to see him, and they receive the first commission to proclaim the resurrection.

Mark’s mysterious Jesus can walk on water, as only G-d can do, but cannot perform miracles in Nazareth because the people do not believe in him. Mark’s focus is on Jesus’s suffering and death; the Gospel’s earliest versions depict the women fleeing from the empty tomb and leave the proclamation of the resurrection to the readers.

Luke’s Jesus is a storyteller (the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan, etc. appear only in the 3d Gospel) who forgives the people crucifying him, comforts the men dying with him, and calmly states, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” While in Mark and Matthew Jesus dies surrounded by his enemies, Luke depicts the “daughters of Jerusalem” weeping for him and the people standing by him.

In Mark and Matthew, the Jesus cries Psalm 22.1, “My G-d, my G-d, why have you forsaken me?” Conversely, John’s Jesus always remains “one” with the Father. According to John, the dying Jesus establishes a new family between his mother and his Beloved Disciple, a family modeled by followers who are “born anew” or “born from above.” According to John, a soldier thrust his spear into Jesus’s side; from the wound pour blood and water, a parturition image suggesting that Jesus is birthing his new family.

How did your work teaching Vanderbilt Divinity School courses at Riverbend Maximum Security Institute influence your consideration of the two men who were crucified with Jesus?

My insider students consistently ask about the men crucified with Jesus: who stood by their crosses to comfort them, to drive away the birds and wild animals, to mourn? Who recovered their corpses and buried them? My insider students help me to complicate the common identifications of “good thief” and “bad thief,” to recognize the desperation of the man who demands of Jesus, “Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” together with the irony that Jesus, by dying, is for the Gospel “saving” — giving life to — humanity. They see the additional irony in the other man’s plea that Jesus welcome him into his kingdom, since this man is the only person in the Gospel who understands that Jesus has a “kingdom.”

Which reactions to “Witness at the Cross” from Christian readers are most common? Which have surprised or intrigued you the most?

Comments in emails, zoom programs, and presentations include gratitude for talking about the women at the cross (Mark 15 tells us that women followed Jesus from Galilee; now I have to incorporate their presence in the previous 14 chapters), for noting various ways of understanding Psalm 22 and the tearing of the Temple curtain, for flagging connections between the crucifixion and earlier Gospel chapters, so that second readings are richer, and for the freedom to appreciate differences rather than jumping through hoops to create harmonization.

Since October 7th and the news from Israel/Gaza, several people have commented on the Introduction’s discussion of Simon of Cyrene, and of Libya’s now-vanished Jewish community.

What books are you reading at the moment?

Marc Brettler and I are now editing the third edition of the Jewish Annotated New Testament. I am reading newly commissioned essays as well as editing revised versions of annotations and earlier essays. After a full day of work, I can’t read anything more. I am knitting a baby blanket for a former graduate student’s newborn son.

Thank you.

You’re welcome.

More to come . . .

DJB

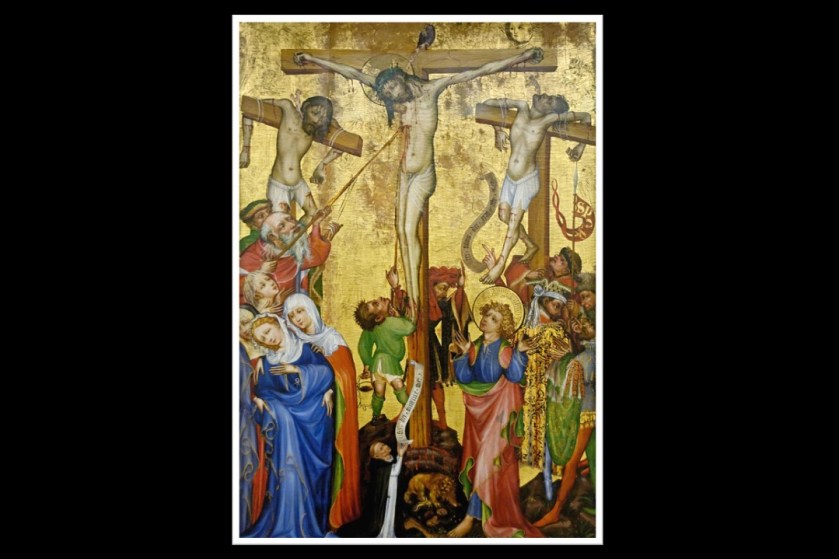

Crucifixion by a Strasburgian painter, possibly Hermann Schadeberg; photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009), Public Domain (Wikimedia Commons)

Pingback: From the bookshelf: February 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . March 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Our year in photos – 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Conversations with writers: 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The best of the MTC newsletter: 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The transformational power of place, art, and story | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Pull up a chair and let’s talk | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Nativity stories that provoke, encourage, and perhaps even inspire | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Readers choice: The best of the 2025 MTC newsletter | MORE TO COME...