There are times when those who are paying attention feel that present and past have merged. Our current political and social unrest has echoes of the 1850s, when a simmering crisis boiled over in the last few months of 1860 and first few months of 1861 to tear apart a divided nation.

History, as we’ll hear often over the next few months, doesn’t repeat but it can instruct. One of our more successful popular writers has turned his attention to this earlier period of American strife, hoping that by immersing ourselves in that era, we can learn how best to turn away from the discord in today’s world.

The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War (2024) by Erik Larson examines the motives and actions of a small minority of rich white men who decided that slavery—and the lavish lifestyle owning other human beings enabled for them and their families—was worth defending to the point of tearing the country apart. In his familiar storytelling style, compelling the reader to keep turning pages, Larson focuses on the chaotic months between Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency on November 6, 1860, and the Confederacy’s shelling of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Much like other times of conflict, it is a period marked by “tragic errors and miscommunications, enflamed egos and craven ambitions, personal tragedies and betrayals.”

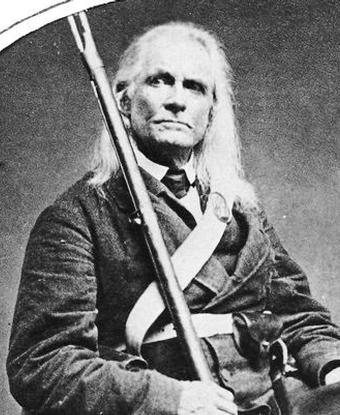

Lincoln, and his growth from politician to leader, is at the center of the saga as he grapples with the heartbreak of taking over a nation that is coming apart while trying to control his “duplicitous” secretary of state, William Seward, who fervently believes he should have been in the White House as opposed to this uncouth, small-town Illinois lawyer. The other key characters are Major Robert Anderson, Fort Sumter’s commander and a former slave owner sympathetic to the South but loyal to the Union; the Fire Eater Edmund Ruffin, a “vain and bloodthirsty radical who stirs secessionist ardor at every opportunity”; and Mary Boykin Chesnut, “wife of a prominent planter, conflicted over both marriage and slavery and seeing parallels between them.”

Anderson is an honorable commander who moves with skill but also makes decisions that leave few good options for his troops. As one of his officers writes home, “We are to be left to ourselves as a sacrifice to turn public opinion against those who attack us.” He knew that the “first gun fired at the fort will call the country to arms.” Anderson’s decisions, in Larson’s telling, are often second-guessed by Capt. Abner Doubleday, an ardent abolitionist from New York who tired of negotiations with the rebels. Anderson is the public servant who, at key points in the saga, loses the forest for the trees, but nonetheless does his duty.

Ruffin and his fellow Fire Eaters are determined to tear apart the Union, plunging America into a devastating war they were never going to win. Traveling from state to state with his unruly white locks of hair and displaying a pike taken from John Brown as a warning to slave holders, Ruffin’s persona is designed to both shock and bring all attention to himself—a period Steve Bannon, one might suggest. His intellect is evident, but his personal demons and unquenchable need for affirmation drive him to push the country over the precipice, a leap he finally takes himself after the war ends.

Chestnut, whose dairies are well-known to historians of the Civil War period, follows her planter husband to Montgomery during this period, where Larson details the whirlwind social activity of the Southern oligarchy. She does elicit some sympathy for recognizing the bonds which bind both women and slaves, but her observational powers—not to mention empathy—only go so far. She is the beneficiary of a system that robs workers of their liberty, dignity, and life so that a very small fraction of the people can live in unparalleled luxury, not unlike the billionaires and other one-percenters in today’s world.

Larson’s work is not without its problems. For a conflict that he rightly shows was all about slavery (not the “states rights” nonsense that apologists from the 1860s until today use as a smokescreen), there is a surprising lack of Black voices in his narrative. Like other observers, I felt it would have been enriched to inject the words and actions of activists such as Frederick Douglass into this story. And his account of Robert E. Lee’s emotional torment at giving up his U.S. Army commission to join the Confederacy, as well as his description of Lee’s attitudes toward slavery, is more Douglas Southall Freeman than Ty Seidule.

There is, however, also much to recommend Larson’s take on this period. He acknowledges in an author’s note that he hopes we will read of this time to help grasp the stakes of the abyss that we might stagger ourselves into here in 2024. And as another commentator has noted, Larson’s explanations of how “a closed-loop, delusional culture (ahem, right-wing news ecosystem) can break people’s brains,” is also highly instructive for our times.

The Civil War is endlessly fascinating for both writers and readers. Larson’s work, while not at the level of some of our greatest historians of the era, is nonetheless a worthwhile addition.

More to come . . .

DJB

Image of Fort Sumter under attack by Currier & Ives/Library of Congress

Pingback: Observations from . . . July 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: July 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...