Americans have long prided themselves on being a democracy that has not devolved into an empire. Our origin story tells how we threw off colonial rule to set our own course in history. And we are quick to point to legitimate efforts to support other countries, be it the Marshall Plan following the destruction of World War II or JFK’s Peace Corps.

But as is the case with most national myths, the truth is much more layered and complicated. Take the Cold War, for instance. While the battle between the U.S. and Russia began in Europe, from the early years much of the conflict “took place in precisely those regions of the world that the Europeans had competed for during the age of the New Imperialism.”

In fact, viewed from the perspective of those regions, the Cold War looked a lot like a traditional imperial rivalry, just bigger and with different protagonists. It was perhaps only to be expected, therefore, that the tactics adopted by Americans in the contest for what they called (using a French coinage) the ‘Third World,’ such as covertly working to overthrow governments deemed hostile to US interests or using counterinsurgency to defend others regarded as friendly, resembled and sometimes even borrowed directly from those of the European colonial powers.”

And just as those European colonial powers discovered, actions taken halfway around the world in some country that most Americans couldn’t locate on a map “had a way of boomeranging home, affecting domestic US life in a myriad of unexpected ways.”

We forget this layer of history at our peril.

The CIA: An Imperial History (2024) by Hugh Wilford sheds important and eye-opening light on an agency shrouded in secrecy and cloaked in conspiracy theories. With memorable characters, eloquent prose, and a well-researched story, Wilford’s new work will appeal to both scholar and the general public. This is a thoughtful look at a little-understood aspect of the CIA’s history—its ties to European empires and America’s own imperial instincts.

Wilford notes that there are many excellent histories of the CIA. The scholarship around American empire—or America in the world—is also growing, and in this latter category he calls out for special recognition Daniel Immerwahr’s excellent How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States which I enthusiastically reviewed in 2020. But none of these works, in Wilford’s estimation, brings the two subjects together. This book is his attempt to make that connection.

Wilford begins with a look at the imperial precursors to the CIA including Napolean; the British secret services, M15 and M16; spy novels by Rudyard Kipling which spun romantic tales of the exploits of spies in faraway lands; and of intelligence legends such as T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia). The early founders of the CIA either came from or often molded themselves on a social class that already shared British imperial values.

While the book follows a rough chronological order, its focus is more on the themes that will help us understand Wilford’s thesis. Looking at the era of the 1940s into the 1970s, he considers intelligence gathering (the Agency’s original postwar function) and how it grew, especially with the help of some old colonial powers. Regime change and regime maintenance come next, American activities we saw in spades in Southeast Asia, Central and South America, and Africa. Moving more to the home front, Wilford then examines counterintelligence, publicity, and those unintended consequences that always seem to boomerang back on the domestic front. The book ends with an update to the “Global War on Terror” and the CIA’s role in the fiascos and occasional successes in the past twenty-plus years since they missed the gathering threat of Osama bin Laden and 9/11.

For each of these chapters, Wilford selects an individual officer to represent the type of operation in question. This makes the thesis easier to follow and puts it into a context for many readers not especially familiar with the subject matter.

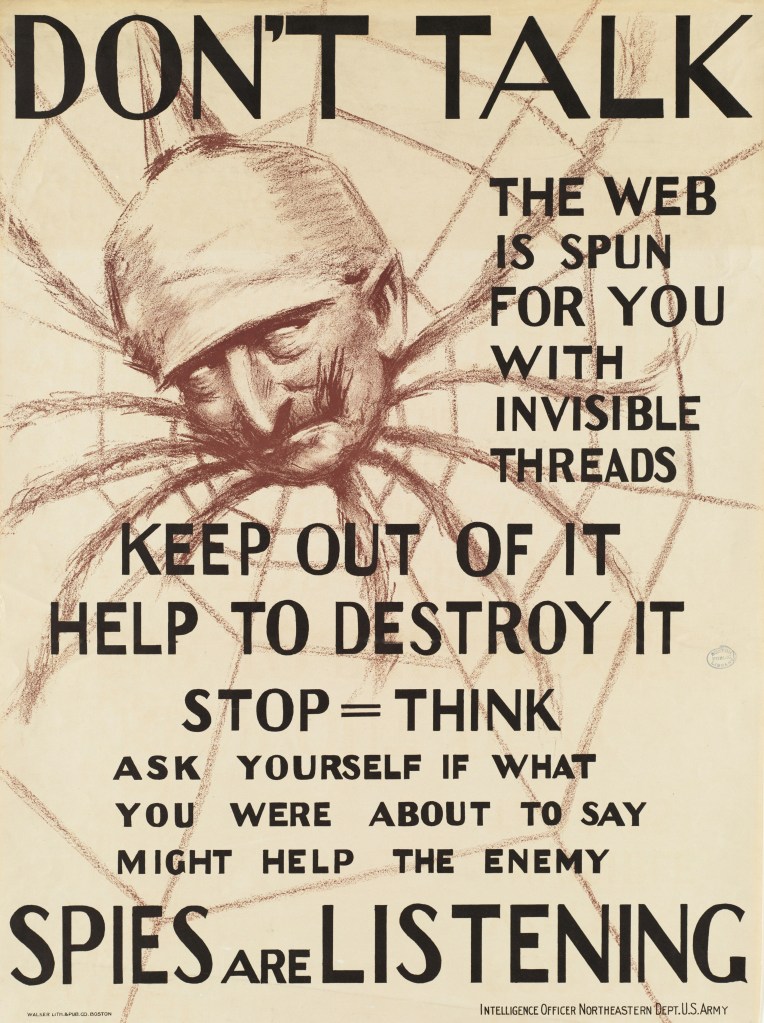

As long as we have been a country, Americans have had parts of the government that spied on both the enemy and suspected traitors, especially during wartime. Wilford makes the case that when the United States defeated Spain in the 1898 Spanish-American war and annexed several Spanish island colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific, it was a small but important step in cementing “in positions of power within American society a distinct imperial class of citizenry that consciously borrowed its values from the British Empire: an elite of white Anglo-Saxon Protestant men inculcated with the ideals of imperial manhood at a select group of eastern seaboard schools.” It was from this class, alongside the children of missionaries (“mish kids”) who had a strong anti-colonialism bias, that the CIA recruited its first cohort of leaders.

After the end of World War II, with the collapse of the colonial empires and the rise of Russia as a nuclear-armed superpower, the CIA was born. Created during the administration of President Harry Truman, who was naturally suspicious of secret government power and later confided to an interviewer that he had come to think of his creation of the CIA as ‘a mistake,’ the Agency at first was surprisingly reluctant to employ its new covert capabilities, perhaps because of the mish kids influence. But that quickly changed because of the leadership of several early founders of the CIA who came more from the British “imperial manhood” mold.

The story Wilford unfolds is riveting and bipartisan. Presidents of both political parties engage in covert activities, some of the most egregious in terms of the boomerang effect being Ike’s engagement through the CIA in Iran, JFK’s fixation on Cuba, Johnson’s undercover work to build up our presence in Southeast Asia, and Reagan’s Iran-Contra shenanigans.

At a time when we are debating the importance and very future of democracy, The CIA: An Imperial History is timely, informative, at-times deeply troubling, and an altogether vital work about the often unintended and disastrous effects of unaccountable power.

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo by Sander Sammy on Unsplash

Pingback: From the bookshelf: August 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . September 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...