NOTE: This is Part 1 of a two-part “Observations from . . .” review of our recent trip to the Greek Isles. Part 2, which will be primarily pictures, will follow on Tuesday or Wednesday.

Last week I was wrapping up another magical National Trust Tours trip with a lecture focused on saving historic places in a changing world. It was the final day of our visit to the Greek islands, the Meteora monasteries, and Ephesus.

We had certainly seen places where, as the philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus (535-475 BCE) phrased it, “the only constant in life is change.” The question I posed to our travelers was this: If old places help ground our memories, define our identity, and place us in a larger continuum of time—providing the backdrop for the narrative each of us creates out of our own lives to make them meaningful and coherent—how might constant change influence our perception of history, the places we remember, and those narratives?

There was also a subtext of “we need better myths” in my remarks. I’d been thinking about myths since Dartmouth professor Aine Donovan’s lecture earlier in the trip on the relevance of Greek philosophy in 2024. So much of history is built on myths and perspectives that can and do change over time. I learned a great deal about history from my beloved grandmother, but as I grew older and studied the facts I had to unlearn the myth of the “Lost Cause” she taught me. My narrative had to change.

Throughout the week we saw beautiful and unique places where history continues to unfold while myths are both strengthened and challenged. Here are a few.

Meteora

A few miles northwest of the town of Kalabaka, the impressive rocks of Meteora rise from the plains of Thessaly, creating one of the most breathtakingly beautiful landscapes in Greece. Centuries ago one of the country’s most important monastic communities formed on these gigantic rocks. The Greek word Meteora means “suspended in the air” and this phrase aptly describes these remarkable Greek Orthodox monasteries.

We visited this UNESCO World Heritage Site on the first day of our tour. Monks began settling on these “heavenly columns” from the 11th century onwards where they eventually built as many as twenty-six monasteries despite facing unimaginable difficulties during construction. For hundreds of years, most of these monasteries were accessible only by a system of wooden ladders, ropes, and buckets. While they continued to flourish until the 17th century, only four still house religious communities today.

Thankfully today’s visitor generally has solid roads and steps . . . hundreds of steps . . . to access these world treasures.

The protection of Greece’s cultural heritage became a government responsibility early on in the creation of the modern Greek state under the supervision of the General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage. We saw that work firsthand, as the government was the funder and driver of the remarkable conservation of the monasteries.

Meteora is a spiritual place, where one engages with nature, God, and man. If we think of heritage conservation at historic sites as focused on both the body (the physical fabric) and soul (the sum of the history, traditions, memories, myths, associations, and continuity of meaning connected with people and use over time), Meteora is “body and soul” in the extreme.

I think the UNESCO nomination gets it right:

“Meteora is one of those places where natural and cultural elements come together in perfect harmony to create a natural work of art on a monumental, yet human scale.”

Ephesus

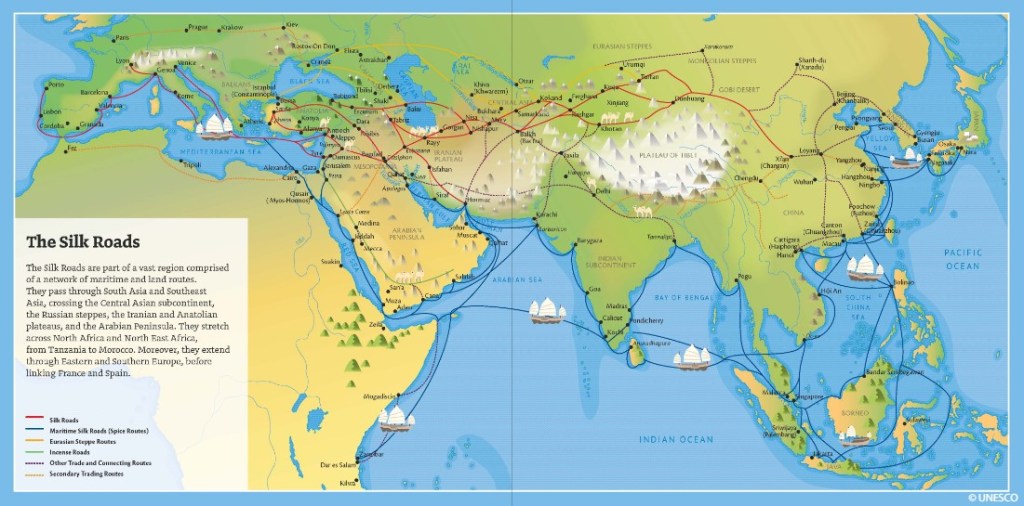

We’ve all heard about the vast trade networks of the Silk Roads. The constant movement and mixing of populations brought about the widespread transmission of knowledge, ideas, cultures and beliefs in addition to carrying merchandise and precious commodities.

We slipped out of Greece into Turkey to visit Ephesus, one of the network’s termination points where ships then carried goods via the Maritime Silk Road—an extension that continued their distribution to further locations around Europe and Asia. And we also saw an incredible mixture of cultures—Asian, Turkish, Greek, and Roman among others.

Science, arts and literature, as well as crafts and technologies were shared and disseminated into societies along the lengths of these routes, and in this way, languages, religions, and cultures developed and influenced one another. The Greeks had a strong influence along the East and West trade route, leading to their engagement and settlement throughout Central Asia. They were also strongly influenced by other cultures.

“Located within what was once the estuary of the River Kaystros, Ephesus comprises successive Hellenistic and Roman settlements founded on new locations, which followed the coastline as it retreated westward. Excavations have revealed grand monuments of the Roman Imperial period including the Library of Celsus and the Great Theatre. Little remains of the famous Temple of Artemis, one of the “Seven Wonders of the World,” which drew pilgrims from all around the Mediterranean. Since the 5th century, the House of the Virgin Mary, a domed cruciform chapel seven kilometres from Ephesus, became a major place of Christian pilgrimage.“

UNESCO World Heritage Site nomination

The extensive archaeological excavations at the Terrace Houses—luxury Roman Villas located on a slope opposite the Hadrian Temple, with the earliest dating from 1 BCE—were among the most impressive I’ve visited anywhere on my travels.

Paul Goldberger notes that “Successful preservation makes time a continuum, not a series of disjointed, disconnected eras.” In a world that is constantly changing, old places—including large archaeological sites of changing communities that have attracted residents, visitors and pilgrims for millennia—provide people with a sense of being part of a continuum, which is necessary to be psychologically and emotionally healthy.

Ephesus was one of those special historic places for us.

Rhodes

Rhodes has incredible layers of history that are key to memories of Christians, Jews, and Muslims. A UNESCO World Heritage Site and the largest of a group of regional islands, it was occupied by the Knights of St John of Jerusalem who had lost their last stronghold in Palestine in 1291. They transformed the island capital into a fortified city able to withstand sieges and to continue their work to care for the sick, but it finally fell to the Ottomans in 1522.

The medieval city—like many of this period—is located within a long wall and is divided with the high town to the north and the lower town south-southwest. Originally separated from the lower town by a fortified wall, the high town was entirely built by the Knights. The famous Street of the Knights is one of Europe’s finest testimonies to Gothic urbanism.

The palace of the Grand Master of the Knights is a restored showpiece that speaks to the power of the Knights of St. John.

The lower town is bustling with shops, houses, and more—all set within the context of the ever-present walls and impressive stonework.

It is important to recognize the layers of history and development in Rhodes that up to 1912 resulted in the addition of valuable Islamic monuments, such as mosques, baths and houses. Old-style renovation projects often sought to erase the destructive evidence of time and circumstances in favor of fidelity to the original place. But to confront and understand our history, it is best if our restorations and renovations leave parts of our past visible—even parts that we may not want to see. We gain knowledge and greater understanding of our world with a multi-layered look at the past. That type of approach was evident in Rhodes.

IN ETERNAL MEMORY OF THE 1604 JEWISH MARTYRS OF RHODES AND COS WHO WERE MURDERED IN NAZI DEATH CAMPS.

JULY 23, 1944.

Pátmos

Perhaps no Greek island is more famous than Pátmos, where we toured the Greek Orthodox Monastery of St. John, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the Cave of the Apocalypse, where St. John the Apostle most likely wrote the Book of Revelation in 95 A.D.

The monastery is a unique creation, integrating monastic values within a fortified enclosure, which has evolved in response to changing political and economic circumstances for over 900 years. It has the external appearance of a castle, with towers and crenellations. It is also home to a remarkable collection of manuscripts, icons, and liturgical artwork and objects.

The Cave of the Apocalypse attracted a number of small churches, chapels, and monastic cells through the centuries, creating an interesting architectural ensemble as well as a place of pilgrimage which we saw firsthand while on site.

The old settlement of Chóra on the island, which surrounds the Monastery of St. John, is also important as one of the best preserved and oldest of the Aegean settlements. Beginning in the 13th century, the town was expanded by new quarters for refugees as political fortunes changed. Interestingly, Pátmos thrived as a trading center under Ottoman occupation, reflected by fine merchants’ houses of the late 16th and 17th centuries.

The elements of the site are unique in several ways, considered both as an ensemble and individually. Pátmos is the only example of an Orthodox monastery that integrated a supporting community from its origins, a community built around the hill-top fortifications.

Authenticity is critical to any historic site. Here the active monastic community of Pátmos, apart from safeguarding the artistic and intellectual treasures of the monastery, continues to rescue old traditions and rituals. And there is cooperation between secular and ecclesiastical authorities in Pátmos, efforts we saw that have ensured that many of the tourism abuses found in other parts of the Aegean have been largely avoided here. This was the one site that was not overwhelmed by over-tourism during our visit. The engagement of a variety of local, state, national, and international actors seeks to maintain the tranquility appropriate to the sacred values of Pátmos in a changing world.

A trip ripe with memories, identity, and continuity

Pico Iyer says that “you don’t travel in order to move around—you’re traveling in order to be moved. And really what you’re seeing is not just the Grand Canyon or the Great Wall but some moods or intimations or places inside yourself that you never ordinarily see.”

Iyer’s quote about why we travel is useful in thinking about changing perspectives and how the places we’re seeing relate to the communities we’ve now returned to after the tour is complete.

More to come . . .

DJB

Top photo of Meteora by Getty Images from Unsplash. All other photos by DJB unless otherwise credited.

Pingback: The wonder of blue harbors, steep cliffs, ancient windmills, and tiny chapels | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . October 2024 | MORE TO COME...