NOTE: This is Book Week at MORE TO COME. As we come to the end of the year, I will have one post each day to close out my reviews and to showcase the 60 books I read during 2024. Today’s entry looks at the art of Johannes Vermeer for clues as to what was happening historically at the time it was produced.

When a brilliant friend recommends a book saying, “It’s the kind of history I wish I could write,” I pay attention. I’m so glad I did.

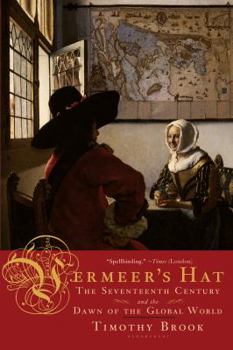

Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World (2008) by Timothy Brook is a work of history that opens up the world for the reader. Using the paintings of Johannes Vermeer, Brook encourages his reader to view certain objects as doors which we can “step through into the teeming social, economic and political context which lies beyond.” Those doors include a beaver hat, Chinese porcelain, a geographer’s map, an African servant, and more. Once we step into these worlds, Brook then deftly explains how the early years of the seventeenth century took mankind from isolated communities to interconnected worlds. It is, as one reviewer noted, an exhilarating piece of history.

Let’s begin with that hat, for it is here where Brook introduces this exploration of globalization. The painting, which adorns the cover, is Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl, dating from around 1658. Brook explains how hats became ubiquitous during this period, and especially once the East Canadian fur trade opened up in the 1610s. Beavers were the fur of choice and the transition in Dutch society—‘from military to civil society, from monarchy to republicanism, from Catholicism to Calvinism, merchant house to corporation, empire to nation, war to trade”—put the Dutch in a favorable position to build extensive trading connections to the wider world.

Each chapter takes a similar tour through the door of an object into the wider world. Five come from Vermeer paintings, while three others relate to objects or the work of a different artist. A porcelain dish holding fruit takes us into the trade wars between the Spanish, English, Portuguese, and the Dutch. A simple figure of a Chinese smoker, produced by a European porcelain maker, sets the stage for a deep dive into the history of smoking and how it shaped and reshaped the world. In each chapter, Brook delves deeply into what was taking place around the globe to help us understand the interconnectedness of our world.

“Brook’s point, really, is that while most of the figures in the paintings of the Dutch golden age look as if they have never strayed more than a day or two from Delft, the material world through which they move is stuffed with hats, pots, wine, slaves and carpets that have been gusted around the world by the twin demands of trade and war.”

Kathryn Hughes

In his very first examination of a Vermeer painting, the View of Delft painted in 1660 or 1661, Brook explains his motive.

“[T]he paintings into which we will look to find signs of the seventeenth century might be considered not just as door through which we can step to rediscover the past, but as mirrors reflecting the multiplicity of causes and effects that have produced the past and the present. Buddhism uses a similar image to describe the interconnectedness of all phenomena. It is called Indra’s net. When Indra fashioned the world, he made it as a web and at every knot in that web is tied a pearl. Everything that exists or has every existed . . . is a pearl in Indra’s net . . . Everything that exists in Indra’s web implies all else that exists.”

Later, in his history of smoking, Brook asks us to think about the seventeenth-century world as Indra’s net . . .

“. . . but one that, like a spiderweb, was growing larger all the time, sending out new threads at each knot, attaching itself to new points whenever these came into reach, connecting laterally left and right, each new stringing of a thread repeated over and over again.”

Behind the china and glinting silver that appear in Vermeer’s paintings “lay real-life narratives of roiling seas, summary justice and years of involuntary exile.” Everything is connected, and “many things were swept along in the movement of people who traveled across the globe without anyone intending that this should happen,” asserts Brook, “remaking the world in ways no one thought possible.” It is a fascinating tale, and one well worth reading and understanding.

More to come . . .

DJB

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . December 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: December 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Exploring the Dutch waterways | MORE TO COME...