Narratives help us understand our lives and our history. Some narratives become so ingrained in our national story that it is difficult to dislodge them, especially when they are used to justify a perspective or long-held prejudice. The Chinese saying that “much of what we see is behind our eyes” speaks to the truth that we often work so hard to force events into our preconceptions that we miss what is right in front of us.

Sherman’s famous March to the Sea in 1864 continues to be framed, as it was for much of the twentieth century, as an early instance of total war. As hard as Sherman wanted to make the war, he never targeted civilians outright and his March was never as horrific as the bombing of Dresden or the Rape of Nanjing. For scholars the issue is mostly settled, even if the question persists in the minds of many Americans. That’s why a new book that works to understand Sherman’s March is so valuable. It reimagines the March’s history “by seeing it for what it truly was: a veritable freedom movement.”

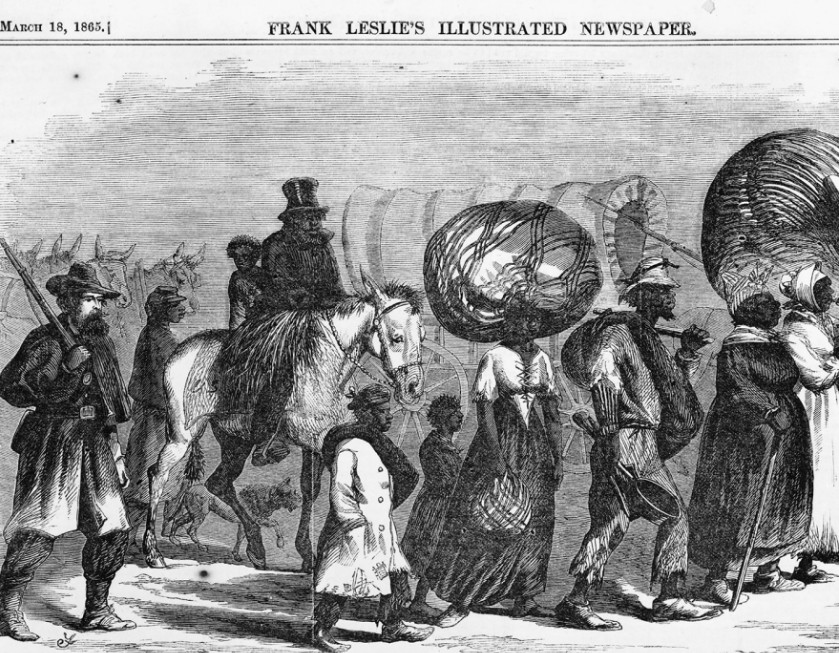

Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation (2025) by Bennett Parten makes the compelling case that this seminal event in the Civil War—when Sherman’s army cut a path through Georgia from Atlanta to Savannah—was a turning point in the history of American freedom. When as many as 20,000 formerly enslaved men, women, and children followed the army as war refugees, it was the largest emancipation event in our history. Because of its wide impact and long-lasting aftereffects, we can now see Sherman’s March not only as one of the last campaigns of the Civil War, but also an early battle of Reconstruction. It is important because we continue, here in the 21st century, to live with the consequences of this march toward freedom.

Author Ben Parten graciously agreed to chat with me about his new work.

DJB: Ben, “Somewhere Toward Freedom” challenges many of the traditional military and political frames for the history of Sherman’s March to the Sea. What first drew you to study this period in America’s story and when did you begin to recognize the hidden history of the March?

BP: I think there are two things that drew me to the Civil War Era. First and foremost, I grew up in Georgia, where much of the war happened here in my own backyard, so to speak. As you know, I’m sure, it is hard to drive around Atlanta and Georgia more broadly without seeing traces of the Civil War.

Secondly, when I was younger, one of the first books I can remember reading was a wonderful book on the Civil War called Rifles for Watie by Harold Keith. It was a children’s novel about a U.S. soldier from Kansas, who fights in the west and falls in love with a Cherokee woman from Oklahoma. It was one of the first novels I can remember reading from cover to cover and even wanting to read again and again. As a kid, that was all it took. I was hooked after that.

And that is actually a pretty good segue into how I came to write this book. I was struck while reading E.L. Doctorow’s The March by one of the characters in the story—a freed woman named Wilma Jones, who follows Sherman’s army to Savannah. I immediately began to question how we could tell the story of folks like Wilma Jones from a historical perspective rather than historical fiction—and that is truly how this book was born. Only afterwards did I discover that there were close to 20,000 Wilma Jones, an enormous number, and that’s when I knew I had a bigger story here, that there was this “hidden history” of the March, as you put it, that we could uncover if we shifted our focus to enslaved people.

You’ve asked your readers to reimagine the history of Sherman’s March as a “veritable freedom movement” as well as “the first battle of reconstruction.” What are the most important lessons we learn when we see the history of this seminal event through these lenses?

First and foremost, we are able to see that the desire for freedom on the part of enslaved people pervades the campaign. It is quite clear just based on their actions that they viewed this as a march of liberation, which only underscores the central meaning of emancipation when it comes to understanding the Civil War. This is something we can sometimes take for granted—or something that gets lost in other Civil War histories. But it is very evident in this story of the March.

Another thing we are able to see is just how important enslaved people were to the overall success of the campaign. They weren’t onlookers; rather, they were participants. For example, they served as scouts, intelligence agents, cooks, roadbuilders, guides, and more. The soldiers knew it, too. The majority of them recognized that they had powerful allies in the enslaved people of Georgia and recognized, as one recent podcast host put it, that enslaved people acted as Sherman’s “fifth column” when marching through Georgia.

But there is also a large story to be told about Reconstruction. The fact is that the size of this emancipation event would go on to have an extraordinary influence on the early shape of Reconstruction. So much of Reconstruction’s early designs all have storylines that point back to the March, but we can only see this connection if we first recognize the campaign for what it was—a freedom movement.

You write of how the ages-old idea of Jubilee became an overarching metaphor for our Civil War, creating a redefinition of American freedom largely led and articulated by people who had been enslaved. Why was the March both a great watershed and also a missed opportunity? How do we continue to grapple with the consequences of the unresolved story?

I describe it as a watershed because, again, the size and scale of this movement was one that couldn’t be bottled back up again. That combined with Sherman’s Special Field Orders 15, which initiates land reform on the coast, uncorks the possibility of a wider and more meaningful Reconstruction. In other words, because of this moment and because of the movement of refugees, what freedom could look like after the Civil War suddenly become more expansive. Yet while a window has clearly opened, the window of opportunity closes rather quickly, and I think it demonstrates quite clearly for us the somewhat unfulfilled legacy of both Reconstruction but also the Civil War.

General Sherman was not always a willing participant in the part of the story involving the March as a magnet drawing tens of thousands of formerly enslaved individuals toward freedom. How would you describe his impact on what, in the end, becomes a narrow redefinition of freedom?

This is a great question, and one that I really struggled with while writing this book. The reality is that he is a reluctant liberator. All along he has never seen emancipation as being crucial to the war, has never done much to advance emancipation. That has changed ever so slightly by 1864. He now sees slavery as an institution to be targeted in an effort to advance the U.S.’s war aims—and is slightly more open to following through on emancipation.

But on the whole he still sees it as of secondary importance to the overall success of his campaign and generally does little to encourage the refugees, help them, or prioritize emancipation at all. He simply would rather ignore the issue—in part because he fundamentally didn’t see it as the army’s job to intervene in what he always thought of as a social or political issue. So his inaction here in some ways tamps down on how wide of an emancipation event this could be.

Tell us how your scholarship brings new light and meaning to what historians, preservationists, and others know as the “Port Royal Experiment”?

Well, first of all, I hope that the book sheds some light at all on Port Royal. It is an incredibly important story in the war that too few people know about—at least that’s the sense I have gotten in talking with folks about the book. But the Port Royal Experiment—essentially, a freedman’s colony on the South Carolina coast—has always been portrayed as a somewhat independent story, as being an isolated “experiment” taking part in a fairly isolated corner of the war. But what the books shows is that its future was entirely connected to Sherman’s March because Sherman’s decision to send the refugees there is the variable that completely changed this so-called “experiment.” It’s a decision that will almost overnight turn Port Royal into the site of one of the largest refugee crises of the Civil War.

The classic work on the Port Royal Experiment is a book called Rehearsal for Reconstruction by Willie Lee Rose, a title that tells you all you need to know about why the Port Royal Experiment was so important.

What other books or authors would you recommend to flesh out the story you tell in “Somewhere Toward Freedom”?

- Noah Andre Trudeau’s Southern Storm

- Steve Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet

- Thavolia Glymph’s Out of the House of Bondage

- Chandra Manning’s Trouble Refugee

- David Blight’s Slave No More

Thank you, Ben.

Thanks for the invitation.

More to come . . .

DJB

Engraving depicting Sherman’s march to the sea. By F.O.C. Darley and Alexander Hay Ritchie. Credit: Wikimedia / Library of Congress Print and Photographs Division

Pingback: Observations from . . . February 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: February 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Pull up a chair and let’s talk | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...