We are used to getting our history from books that take deep dives. Works like Ron Chernow’s U.S. Grant or Ned Blackhawk’s The Rediscovery of America. Even on the popular history front, we still expect books like Seabiscuit or The Devil in the White City.

Book publishers often don’t know what to do with a writer who is captivated by “the magic that lies in the liminal spaces between the plot points in people’s lives.” Thankfully, Random House decided that those spaces, which make up much of our time here on earth, are worth exploring as well.

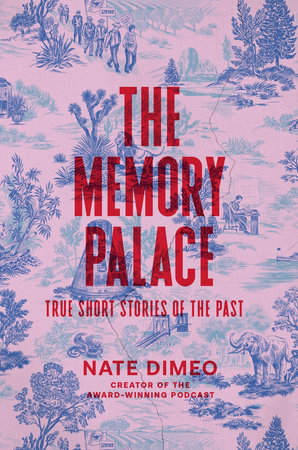

The Memory Palace: True Short Stories of the Past (2024) by Nate DiMeo is a wonder-filled collection of stories from our past. DiMeo, who grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, wears the city’s past—full of Italian immigrants and plenty of places not named Brown or RISD—on his sleeve and in his heart. These “true short stories” are looks into the lives of people, some of them famous but many forgotten by time, whose stories deserve to be known. He looks at these places “between and beyond concrete facts and the well-worn language of familiar stories” to remind us that “life, in the present as in the past, is more complicated and more interesting and more beautiful and more improbable and more alive than we’d realized.” This is a work that surprises and informs and delights all while making us think.

He begins with the story of how Samuel Finley Breese Morse went from being a painter so successful that he was asked to paint a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette to the individual who devoted the last forty-five years of his life inventing the telegraph and the code that is still known by his name. Why? Because while waiting in Washington for his distinguished visitor he received a note from a courier “breathless and dirty from a hard ride and a hard road.” It told him his dear wife was ill. Morse immediately dropped what he was doing and raced back to New Haven—a trip that took six days at that time—only to find that his wife had died even before he received the note. Those forty-five years were devoted to being able to transmit “the stuff of life and of dying wives.”

We learn of how Giovanni Schiaparelli “discovered” canals on Mars in 1877, a find that captivated people from New York to Sydney and scientists from Cambridge to Jaipur. Percival Lowell, the son of one of the wealthiest families in New England, confirmed that from a telescope in Flagstaff, Arizona, but he took it one step further and speculated that they were built by a civilization on par with our own. It was, alas, a case of seeing what we want to see. Schiaparelli had used the word “canali” by which he meant “furrows” but which was mistranslated by Lowell and most of the English speaking world. By 1907 enough scientists had reviewed the findings and picked holes in his evidence. Lowell’s work was important but in the end he went looking for canals and that’s what he saw. So there were canals on Mars . . . at least from 1877-1907.

The book is full of such stories.

“A socialite scientist who gives up her glamorous life to follow love and the elusive prairie chicken. A boy genius on a path to change the world who gets lost in the theoretical possibilities of streetcar transfers. An enslaved man who steals a boat and charts a course that leads him to freedom, war, and Congress. A farmer’s wife who puts down her butter churn, picks up the butter, and becomes an international art star.”

DiMeo ends his book with six origin stories, pieces drawn from his life as a younger person. And there, in the Federal Hill neighborhood of Providence and the surrounding landscape, we discover what drives his passion. He came to the realization that we are all products of the historic moments we are given.

“That in a different era maybe I wouldn’t be thinking about going to college; maybe I would be drafted into a war, or would be getting on a boat, hoping to find a place by a river to put a barbershop; maybe I wouldn’t be getting an easy cure for my Graves’ disease. I wouldn’t be meeting these friends. Now. This is our moment . . . These were the lives we got to live. Timing was everything, it turned out, and it was a gift to notice beautiful moments as they happened, but I felt alone in holding that particular melancholy of knowing they were, in that same moment, becoming the past.”

DiMeo realized that telling these stories well was what mattered. Tight, sharp remembrances infused with meaning. By doing so, he felt connected, and in the process he has connected all of us.

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

Pingback: Observations from . . . April 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: April 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...