My first 2025 trip as an educational lecturer with National Trust Tours was an exploration of Holland and Belgium along with Dutch waterways. It was an initial introduction to the Low Countries and Flanders (the Dutch-speaking portion of Belgium) and we enjoyed having time to dip our toes into this fascinating part of the world that has always been near the center of a web of history.

The places we visited were often conceived from an expansion of global connections. Trade was key to the growth of both The Netherlands and Belgium beginning at the dawn of the 17th century, a salient point made in Timothy Brook’s exhilarating Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeen Century and the Dawn of the Global World.

Touching lightly on the places that moved me

While I posted deep-dives on specific places late last week* I’m going to take this opportunity to bring the disparate pieces of the tour together in a light wrap-up to highlight a few additional places that really moved me. Light doesn’t mean short . . . but I’ll make it as brief as possible.

Monumental Kerks, magnificent musical instruments, and beautiful train stations

An uneventful flight (the best kind) brought us to Amsterdam bright and early on an April Monday morning. By the afternoon we were exploring the Portuguese Synagogue, the Jewish Quarter and other parts of the Canal District, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Great churches (called kerks in Dutch) are at the heart of cities in both Holland and Belgium. The next day we eagerly took in the Westerkerk, where—as is our custom—we gravitated to the organs. In 1681 the Westerkerk commissioned Roelof Barentszn Duyschot to build a new organ. He died before the instrument was complete and his son finished the job. In 1727 the console was enlarged with a third manual by Christiaan Vater. The small mechanical action choir organ was built in 1963 by the Dutch builder Flentrop.

Rembrandt van Rijn was buried in the Westerkerk on October 8, 1669 but the exact location is unknown. Westerkerk’s impressive spire—the highest church tower in Amsterdam—can be seen throughout this part of the city.

By Thursday we were visiting Nijmegen. Stevenskerk sits at the heart of this historic city and as is often the case, one went through winding streets before the church spire was revealed.

In addition to Amsterdam, Nijmegen, and Antwerp, over the course of the next few days we saw a variety of beautiful churches, both large and small.

One of the most spectacular houses of worship was St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, where—following a terrific lecture by the University of Virginia’s Lisa Reilly—we had the opportunity to view the beautifully restored Ghent Altarpiece (featured in the movie The Monuments Men).

Finally, when it comes to lovely spaces, it is hard to top the train station in Antwerp which is often listed among the most beautiful in the world. I would agree.

Belfries, street patterns, and the loss of landmarks

There are fity-five belfries in Belgium and the North of France inscribed on the World Heritage List. The ensemble dates from between the 11th and 17th centuries and includes a range of architectural styles.

As a group, the belfries are highly significant tokens of the winning of civil liberties. While Italian, German and English towns mainly opted to build town halls, in this part of north-western Europe greater emphasis was placed on building belfries. Compared with the keep (symbol of the feudal lords) and the bell-tower (symbol of the Church), the belfry symbolizes the power of the aldermen and civic government.

Over the centuries, they came to represent the influence and wealth of the towns. These central belfries have played a pivotal role in the development of the urban landscape right up to present times.

Brugge is an outstanding example of a medieval historic settlement where the original Gothic construction continues to form part of the town’s identity. As one of the commercial and cultural capitals of Europe, Brugge developed cultural links to different parts of the world.

We can still see the exchange of cultural influences on the development of the city’s art and architecture. The medieval street pattern, with main roads leading towards the important public squares, has mostly been preserved, as has the network of canals. While it remains an active city where we can still see the architectural and urban structures which document the different phases of its development, the medieval section does have more of a museum quality than, say, Amsterdam.

Construction of the Ghent belfry began in 1313 and after continuing intermittently through wars, plagues and political turmoil, the work reached completion in 1380. The uppermost parts of the building have been rebuilt several times, in part to accommodate the growing number of bells. I climbed to the top of the belfry while on our visit and had outstanding views of the city.

A major element of the cities where they are located, belfries were also a weak point; a symbol and sometimes a watchtower, they were regularly destroyed during armed conflict. It is impossible to consider authenticity only in material terms, referring only to their initial period of construction.

Instead, UNESCO considers the permanence of the existence of the belfries and their symbolic value as authentic. The reconstructions following the world conflicts of the 20th century are exemplary and constitute an important element of authenticity.

War and natural disasters are facts of human existence. We’ve seen world landmarks lost—think of Notre Dame in Paris—whole cities destroyed (in the US think of the Great Chicago Fire or the San Francisco earthquake), and we’ve recently seen landscapes, towns, and cities overwhelmed by wildfires in Los Angeles. In each of these instances, we lose historic resources and have to make decisions about their future and how we remember the stories they hold.

Memorials

When issues around the demolition of landmarks or the removal of statues and monuments are raised during my lectures, I note that instead of “destroying” our history, what we may be doing is readjusting that part of the past that we are choosing in the present to remember, commemorate, and perhaps celebrate. What we know about history continues to grow. Heritage is also constantly changing and shifting as each generation chooses what part of the past it wishes to commemorate in the present, as we interpret what’s important through different lenses.

It is hard for any of us to see the world as others see it. It is possible, if we work at it, to remember that others see things differently. But we have to want to work at it.

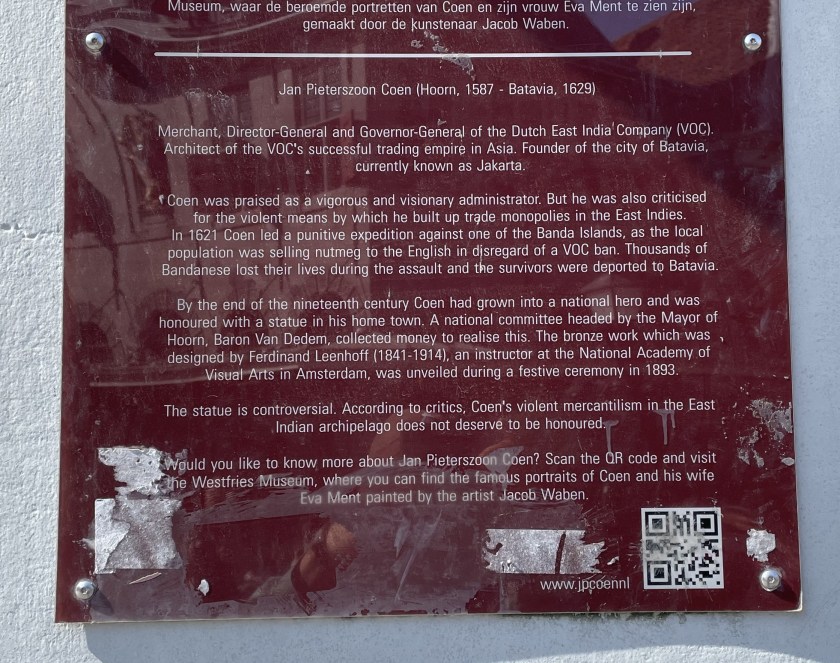

Memorials inevitably bring us face to face with philosophical questions of justice, collective memory, free will, moral culpability, and individual vs. national responsibility. Controversies over monuments and the memories they celebrate are not unique to the United States. We saw a perfect example on this trip.

Jan Pieterzoon Coen was nicknamed the “Slaughterer of Banda” because of his role in the conquest of the Banda islands, in modern-day Indonesia. In 1621 only 1,000 of the 15,000 local inhabitants were believed to have survived the conquest, which was undertaken so that the Dutch East India Company could control the supply of nutmeg.

For that reason, his statue in Hoorn has been a disputed monument from the day of its unveiling in 1893. It has been smeared with red paint and graffiti numerous times in the last six decades. In 2010 a citizens’ initiative pushed for removal and in response a contextualizing plaque was added in 2012. The debate over the monument has not abated, however.

After my lecture I was asked what types of monuments I would like to see erected in place of controversial military figures, and I noted that we’d seen one just a few blocks away earlier that day in Hoorn. On the street that led to the library was a modest yet endearing monument to books.

I think we need more monuments to books.

Hoorn, by the way, was one of my favorite small towns we visited over the ten days. Here’s a sampling of all that we saw:

And finally . . . a personal note

Candice is always great about searching for a stellar local restaurant for us to explore on our first couple of personal days in the city. In Amsterdam she hit a home run, as we savored one of the best meals either of us has ever experienced. Vinkeles, a two-star Michelin restaurant serving modern French cuisine, was a true “gastronomic journey.” Words fail me.

More to come . . .

DJB

*For additional posts on this National Trust Tour, visit:

- Pausing to think is how we sanctify time (The Portuguese Synagogue)

- The transformational power of place, art, and story (A Holy Week visit to the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp)

- The enduring beauty and utility of the windmill (Visiting the Mill Network at Kinderdijk)

- Tulipmania (The Keukenhof Gardens and bassist Joe Leonhart playing The Tulip Song)

Photo at top of post by Getty Images from Unsplash. All other photos by DJB unless otherwise credited.

Sounds like a fabulous trip. Thanks so much for sharing some of the high points and photos.

Thanks, Sarah. It was a terrific trip. Hope to see you and Tom again soon. Take care – DJB

Pingback: Observations from . . . April 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Traveling in order to be moved | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Our journey through Europe | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Our Year in Photos — 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Oh, the places we’ve seen! | MORE TO COME...