There is an unease in today’s world. Our would-be dictators are rushing about severing alliances, sabotaging support, undermining cooperation within the nation and across the world. As Rebecca Solnit puts it,

“It seems to be in their nature to segregate, isolate, and disconnect. They cut the United States off from the World Health Organization and the Paris Climate Treaty. They cut off the countless beneficiaries of USAID programs as they left USAID workers stranded across the world. They cut off crucial parts of the federal government with reckless disregard for how those parts contribute to the functioning of the whole—or maybe with enthusiasm for its malfunction, perhaps because they’re bought into the rightwing idea that all this stuff is unnecessary, obstructive. It’s certainly in the way of some of their ambitions.

In this climate of separation and disconnection, I first became aware of an important new book from Solnit’s mention of it in her Meditations in an Emergency newsletter. Solnit noted that long before our era, the political theorist Hannah Arendt was very familiar with these type of men who seek to tear us apart.

“A few days ago, the Arendt scholar Lyndsey Stonebridge called my attention to this passage from Arendt’s On the Origins of Totalitarianism: ‘What binds these men together is a firm and sincere belief in omnipotence. Their moral cynicism, their belief that everything is permitted, rests on the solid conviction that everything is possible.…Yet they too are deceived, deceived by their impudent conceited idea that everything can be done and their contemptuous conviction that everything that exists is merely a temporary obstacle that superior organization will certainly destroy.’”

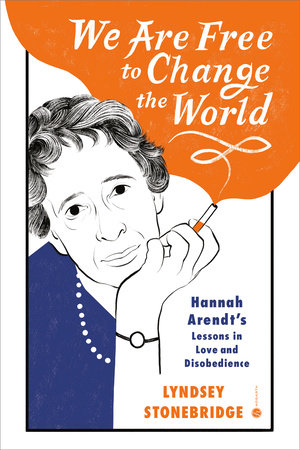

We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience (2024) by Lyndsey Stonebridge is the book we need for these times. A compelling biography but also a primer for how to think if we want to be free. Arendt was not perfect and not always the easiest person to understand, as Stonebridge details, but she thought and cared deeply about humanity. Thanks to Stonebridge’s very accessible and thoughtful writing, readers are brought into Arendt’s world to see why she came to think the way she did. In doing so, Stonebridge takes us from fascist Germany to twenty-first century America.

The subtitle of the work is very important. These are lessons from one of the twentieth century’s foremost opponents of totalitarianism to those of us navigating the slide into what political scientists Steven Levitsky, Lucan Way, and Daniel Ziblatt have labeled “competitive authoritarianism.” As they note in their recent New York Times op-ed, “America’s slide into authoritarianism is reversible. But no one has ever defeated autocracy from the sidelines.” Arendt’s life and work is, in this masterful biography, in a dialogue with today’s turbulent times.

Many of us have only encountered Arendt in short, quotable snippets or perhaps in her famous (or infamous) New Yorker articles on the Adolf Eichmann trial. Stonebridge’s gift is to make Arendt’s work accessible and compelling for our era. As she writes in the first chapter, it wasn’t until she started to work out why we should be reading Arendt in the age of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin that she realized “it was the stubborn humanity of her fierce and complex creativity” that we had most to learn from. Throughout her adult life Arendt was asking one question above all others: What is freedom?

That is also the title of the last of ten chapters in this book, which look at subjects such as “How to Think” and “How to Think—and How Not to Think—About Race,” the latter taking up Arendt’s missteps around racial inequality in America. In a 1959 essay called “Reflections on Little Rock” she criticized the campaign against the segregation of schools in the Jim Crow South. “Written in a lofty and chiding tone, her essay caused a scandal because in it she had forgotten one of her own lessons: you can’t co-create rights and freedom with people who you cannot see.” Hannah Arendt was far from perfect. She “did not know the children of Little Rock, Arkansas, nor did she comprehend the history of their fight.”

Arendt’s work on race simply proves that she was human. Yet her voice is one we should still hear today. Stonebridge talks of how Arendt’s 1958 book The Human Condition was, above all, about bringing people back to earth “so that they could appreciate what they had—and what they had to lose.” She worried that technology and overconsumption were alienating us from the earth. Hers was not the only voice making this case. In an extraordinary passage, Stonebridge notes that in an eight month period the New Yorker published the first installments of Eichmann in Jerusalem, Rachel Carson’s article from her ground-breaking Silent Spring, and a James Baldwin essay that would become The Fire Next Time. Even contemporary readers noted the change in the quality of the magazine’s truth-telling.

“There is a reason why James Baldwin, Hannah Arendt, and Rachel Carson are three of the writers from the last century whose voices speak to us most urgently in our own. They show us, yet again, possibly because people did not pay sufficient attention the first time, possibly because the very things they feared have indeed got much much worse, the beauty and fragility of existence.”

It was the chapter on “How to Love” that told me more about Arendt that one can glean from the anti-authoritarian quotes in memes. “Love is a paradox in Arendt’s thinking,” writes Stonebridge. “Love is what makes us human, plural, alive to one another and to the human condition itself.” It may be all we have. But because of its earthly power, love can be “more than human, possibly inhuman” and politically speaking, very dangerous.

“Love matters in our politics because it matters to us at the most intimate level of our lives. As we do now, Arendt lived in a world where there was far too much passionate intensity of the worst kind, and not nearly enough neighborly love.”

Totalitarianism to Arendt was not just a new system of oppression, it seemed “to have altered the texture of human experience itself.” The crime, which she explored in 1963’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, was against “both large groups of people and against the very idea of human plurality.” Yes, the moral obscenity of the Holocaust had to be recognized, put on trial, grieved, and addressed. But existing methods and ideologies could not make it right. It was the banality with which the crime was executed that needed to be reckoned with, a reckoning that we have yet to undertake.

Early in life Arendt came to see one simple idea that set the stage for her life’s work: “that we think and that how we think has moral consequences.” Embracing perplexity became her first line of resistance against the absolutism that infects totalitarianism. Truth-telling is what you do when you have nothing else. Arendt once observed:

“To be sure, no one understood the rain better, no one showed so clearly what rain was like, than the person who happened to have no umbrella and therefore became soaking wet.”

In the end, Arendt’s work comes back to love and freedom. Nothing, she wrote, “perhaps illustrates the general disintegration of political life better than a vague pervasive hatred of everyone and everything.” Real freedom, which Stonebridge highlights as Hannah Arendt’s central political insight, “requires the presence of others so that we can test our sense of reality against their views and lives, make judgements, probe, and learn.”

Adolph Eichmann, she came to realize, “was thoughtless to the point that he no longer inhabited the real world—which was partly why he could wreck such terror upon it.”

Because we have would-be dictators and tech bros who also no longer inhabit the real world of the 99% of humanity, we are facing the same issues today. This courageous book is definitely a work for our era.

More to come . . .

DJB

For those wishing to go down a rabbit hole, see Peter Michael Gratton’s essay The Banality of Complicity: Arendt’s Guide to Moral Resistance in the Age of Trump as well as Against Strategy: The Moral Stands We Need Today in the newsletter Liberal Currents. To read more about the isolation of citizens and its impact on democracy, read Elise Labott’s A Crisis of Faith. And Not the Religious Kind. in the Preamble newsletter.

Wrong Way sign by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Pingback: Observations from . . . May 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: May 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Grievance, fringe theories, and bad vibes | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...