Before wheelchair ramps, curb cuts, and other such accommodations became standard practice, how did people with disabilities interact with the built environment? Rather than being precluded from participating in modern culture, a new book makes the case that the subjective experiences of people with disabilities were at the generative center of modern architecture.

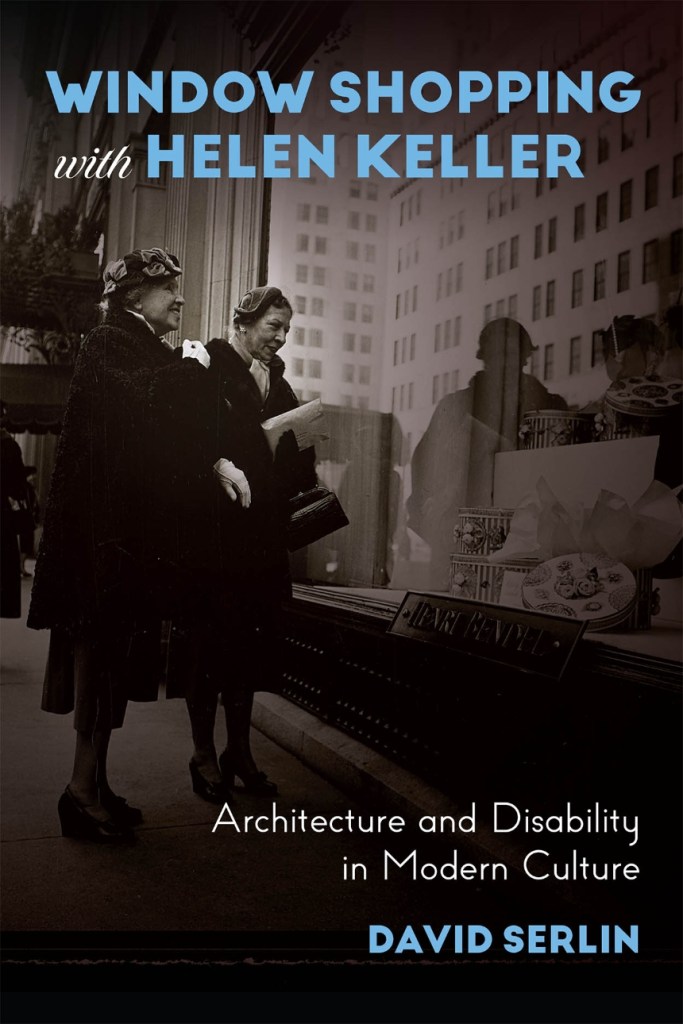

Window Shopping with Helen Keller: Architecture and Disability in Modern Culture (2025) by David Serlin is an academic work from the University of Chicago Press that seeks to reassess modern architecture and urban culture when it comes to addressing the needs of people with disabilities. Serlin’s work draws upon fields as diverse as architectural history, disability studies, media archaeology, sensory studies, urban anthropology, and feminist science studies and as such can too often take the reader on a dense and winding path. Nonetheless, there is plenty here to capture the reader interested in the topic, either from the perspective of well-known historical figures such as Joseph Merrick (aka the “Elephant Man”) in London and Helen Keller in New York and Paris, or for those who want to study institutions and buildings that had outsized influence, such as the WPA and Stanley Tigerman’s Illinois Regional Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Serlin has us consider “a series of influential moments when architects and designers engaged the embodied experiences of people with disabilities.”

In a lengthy introduction followed by four chapters, Serlin argues that there is empirical and representational evidence of “an adjacent universe” in which architects and designers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries “took a keen interest in the embodied experiences of people with disabilities.” Merrick and Keller’s experiences make up the first two chapters. In the third case study Serlin suggests that the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration provided little-known but important services for people with disabilities, both as an employer and as producer of services. The WPA’s capacity to “think about disability as a potentially generative economic, social, and educational opportunity was the last gasp” of a democratic pluralism that evaporated by the beginning of the Cold War.

Publishers Weekly explains more about Serlin’s interest in the WPA.

“As the New Deal institution responsible for so much of the modern built environment, other scholars have pegged the WPA as deeply under the sway of eugenics, incorporating little accommodation for the elderly, infirm, or disabled, but Serlin surfaces evidence that in fact it contained fairly advanced thinking on disability (he especially focuses on architectural and design projects meant to accommodate children suffering from polio-induced paralysis), and that it was Cold War–era design that actually swept away disability-accommodating features.”

In the book’s final chapter Serlin is considering Tigerman’s design of the Illinois Regional Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. He suggests that the architect thought about the disabled as a user—not what their disabilities prevented them from doing but what they made possible.

A point from his introduction is instructive.

“If one measures successful architecture only by the intentions of the designer and not by the experiences of the user, then one is willfully and brazenly ignoring what a user’s perspective can lend not only to the utility of the design but also to its meaning.”

I strongly agree.

Serlin’s book can be difficult to digest, theory heavy, and not for the casual reader. But it is an intriguing work and there is much of value to consider here.

More to come . . .

DJB

Image of Sargent Claude Johnson WPA-commissioned proscenium (1937) for the California School for the Blind in Berkeley (credit: Huntington Museum)

Pingback: From the bookshelf: May 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . June 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...