Some books receive fulsome recommendations that are hard to square with the reader’s actual experience. Others deserve the acclaim that comes their way.

Then there are books—like this one—that deserve all the praise they receive and more.

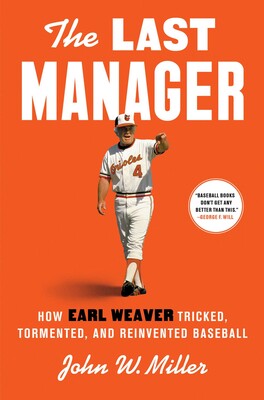

The Last Manager: How Earl Weaver tricked, tormented, and reinvented baseball (2025) by John W. Miller is a splendid new biography of one of the game’s great characters and innovators. Weaver—forward-looking genius, shrewd evaluator of talent, brilliant strategist, superb entertainer, part wizard—is deserving of the royal treatment. The Bismarck of Baltimore came into the game at the twilight of the age of the baseball manager. His uncanny skill at figuring out so many things about the game without the benefit of the computer probably hastened the age’s demise. Now they just program the machines to think like Earl, but they can’t teach them . . . or today’s managers . . . his character. Always quick with the quip Weaver was a quote machine who had a purpose when unleashing his acid tongue. An umpire once offered to give him his rule book; Earl immediately shot back, “No thank you. I don’t read braille.”

They broke the mold with Earl Weaver.

Long-time fans and newcomers to baseball now have this marvelous biography, written by a first-rate reporter who obviously loves the game. Miller provides a more complete picture of this complex individual, beginning with Weaver’s childhood where he was partially raised by a mobster uncle. The “Gangs of St. Louis” chapter was especially enlightening.

Weaver’s deep analysis of games and probabilistic outcomes came as a result of his youth in a culture saturated with gambling. This was an eye-opening revelation, as I have often been a vociferous opponent of gambling in today’s game.

“Americans wagered as much as $5 billion a years on baseball in the 1940s. The sport’s pitch-by-pitch beat of precise, often binary outcomes has always fit gambling like a ball in a glove. In fact, it’s unclear if baseball would have become a popular professional sport without the interest of the gamblers.”

The gambling culture pushed Earl to hone his analytical skills, leading him to grasp probability theory through the prism of gambling. Earl “talked like a bookmaker” according to one baseball executive. I’m still not sure I approve of the legalized gambling in today’s game, but thanks to Miller’s reporting I now have a much better appreciation for its role in the game’s history.

I also enjoyed Miller’s references to Weaver and the classic baseball move Bull Durham. Hollywood director Ron Shelton had been a minor-leaguer in the Orioles system before turning to the movies. One of the stars of the film—hard throwing pitcher Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh—was based on Steve Dalkowski, a real-life prospect who threw harder than anyone else. But he never knew where the ball was going. Plus he drank. Weaver, as his minor-league manager in Elmira, came closest to getting this unharnessed talent to the majors.

“As a minor league manager, Weaver was the only manager who came close to helping legendary pitching enigma Steve Dalkowski become a major league pitcher. Dalkowski is considered among the top handful of hardest thrower pitchers in baseball history, but suffered an extraordinary lack of control. In 1958, Dalkowski struck out 203 batters in 104 innings, but walked 207. Over his minor league career, he walked over 1,200 in 956 innings. However, in 1962, Weaver managed him with the Elmira Pioneers, and worked with Dalkowski to simplify Dalkowski’s approach to pitching. For the first time, Dalkowski averaged less than a walk an inning, and his earned run average was over two runs less than any prior year. Dalkowski was on his way to making the Orioles major league roster the following year when an arm injury effectively ended his career.”

Wikipedia

When introducing the Orioles’ new manager in 1968, general manager Harry Dalton said, “In short, I believe Earl Weaver is a winner.” At 5’7″ Weaver was short. And he was a winner. Much of the book looks in depth at Earl’s time with the big-league club. During those 17 years Weaver had only two losing seasons: his first and his last.

After he took over in Baltimore, Weaver hung a sign in the clubhouse: “It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.” Weaver exemplified this attitude more than most. He changed the way he approached the game based on the players he had. Earl was the only manager to hold a job during the five years leading up to and the five years after free agency upended the sport in 1976. He was able to figure out how to work with the hand he was given.

His famous ten laws of baseball evolved over time, but they show a sharp strategic mind as well an everyman intelligence.

- No one’s going to give a damn in July if you lost a game in March.

- If you don’t make any promises to your players, you won’t have to break them.

- The easiest way around the bases is with one swing of the bat.

- Your most precious possessions on offense are your 27 outs.

- If you play for one run, that’s all you’ll get.

- Don’t play for one run unless you know that run will win a ballgame.

- It’s easier to find four good starters than five.

- The best place for a rookie pitcher is long relief.

- The key step for an infielder is the first one—left or right—but before the ball is hit.

- The job of arguing with the umpires belongs to the manager, because it won’t hurt the team if he gets kicked out of the game.

“Just as Copernicus understood heliocentric cosmology a full century before the invention of the telescope,” Tom Verducci wrote in Sports Illustrated in 2009, “Weaver understood smart baseball a generation before it was empirically demonstrated.”

Finally, as you would expect in a full biography of Earl Weaver, this one is sprinkled with colorful quotes and lots of f-bombs. Just a few of the Weaverisms found in The Last Manager include:

- I gave Mike Cuellar more chances than I gave my first wife.

- The key to winning baseball games is pitching, fundamentals, and three run homers.

- Don’t worry, the fans don’t start booing until July.

- Everything changes everything.

When a young Tom Boswell apologized for interviewing Weaver during the National Anthem, the manager shrugged it off and said, “Don’t worry, this ain’t a football game. We do this every day.”

One of the most famous of Weaver’s run-ins with umpires came on September 17, 1980. First base umpire Bill Haller agreed to wear a mic for a local Washington news show, but Weaver wasn’t aware of that key fact. So when he ran out of the dugout to protest a balk, one of the great manager/umpire arguments of all time ensued, and it was caught on film. Don’t watch this if your ears are sensitive.

Later, of course, Earl could do a spoof with former player Bob Uecker on how to argue effectively with an umpire.

As Orioles pitcher Mike Flanagan said of Weaver when The Earl of Baltimore passed away in 2013: “There’s nobody like him left.”

More to come . . .

DJB

Pingback: Observations from . . . June 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: June 2025 | MORE TO COME...