It is important to continue to put forward searing, difficult histories in the hope that they will break through the malaise of indifference. We hear “never again” to the point that there is a danger these words lose their impact. The genocidal treatment of the Jews during the Nazi-led holocaust, however, is history that should never be forgotten much less repeated. When indifference appears to be universal, this part of the past should always be there to inform and shape our individual and collective responses to evil. As those years recede into history, it is far too easy to stop telling the stories and dismiss the terrors of those times.

Thankfully, we have true accounts of the horrors of those years to shake us out of our complacency. They often demonstrate how easy it is to respond to the demands of authoritarians with self-serving collaborations and justifications.

I just finished one such work that I simply cannot get out of my mind. I write today to recommend it as a book you’ll never forget.

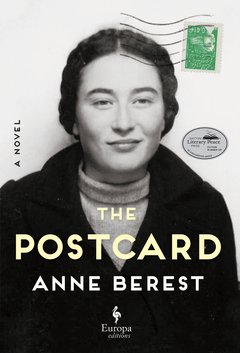

The Postcard (2021; translation from the French in 2023) by Anne Berest is a compelling and timeless work that is so necessary for our current moment. In January of 2003 an anonymous postcard is delivered to the Berest family home, arriving alongside the usual holiday mail. On the front, a photo of the Opéra Garnier in Paris. The back contains only the first names of Anne Berest’s maternal great-grandparents, Ephraïm and Emma, and their children, Noémie and Jacques. There were five members of the Rabinovitch family. These four were all killed at Auschwitz. The fifth—an older sister to Noémie and Jacques—is Myriam, Anne Berest’s grandmother, who never spoke about the loss of her family or acknowledged her Judaism. Although she had a harrowing escape from the Nazis and then worked for the Resistance, she was traumatized; filled with guilt and grieving. After the war Myriam assimilated into France. The quest to uncover who sent the postcard and why leads Anne and her chain-smoking mother Lélia Picabia on a multi-year journey of discovery.

Early in the book Anne—the author and narrator—is on bed rest and about to have her first child. She asks Lélia to tell her what she knows about the family to help her fill in what is essentially a blank canvas.

“These people were my ancestors and I knew nothing about them. I didn’t know which countries they’d traveled to, what they’d done for a living, how old they’d been when they were murdered. I couldn’t have picked them out of a photo lineup.”

What follows is an autobiographical novel full of both pain and grace. The phrase un roman vrai—a true novel—describes what Berest has produced. Lélia is a retired professor who, in reaction to her mother’s silence, has spent her life searching for her family’s history. Her home office is filled with archive boxes of government documents and personal letters. As one commentator notes, the way Lélia speaks to Anne about her story “is a straightforward, effective way to tell readers about the making of the novel they are holding:”

“I should warn you,” she began now, “that what I’m about to tell you is a blended story. Some of it is obviously fact, but I’ll leave it up to you to decide how much of the rest comes from my own personal theories. And of course, any new documentation could flesh out those conclusions, or change them completely.”

In a book that moves along at the “pace of life,” the reader is confronted again and again with scenes that remind us of the psychological and physical terror of the treatment of the Jews in the decades leading up to and including World War II. The Rabinovitch family are Russian Jews who flee their home country as anti-Semitism rises early in the 20th century. Ephraïm and Emma move the family to Riga, Latvia—a place of remembrance for Jews—then to Palestine before finally returning to Europe and settling in France in 1929.

Ephraïm is an engineer, inventor, and business owner who is determined to assimilate his family, working unsuccessfully for years to obtain French citizenship. Emma teaches piano on a treasured family instrument. Noémie, whose photograph graces the cover of the book, is a budding writer whose tragic story of talent lost—a story that holds true for the entire family—clearly touches the author at her core. Jacques is just a young boy of 16 when he is murdered.

The story moves back and forth in time as Anne digs into her family’s past; recreates scenes based on historical fact; uses shifting narrators; and grapples with her relationships between grandmother, mother, and the author’s daughter. As translator Tina Kover notes, “[t]he book is deeply personal, breathtakingly emotional, raw and intense and beautiful. My translation had to be just right.”

“Climbing inside the story of Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques” [writes Kover] “meant that I would suffer their loss, and even though I was prepared for it, translating that part of the book was excruciatingly painful. But the revelation came in the happiness I felt as I was translating their lives. They were vibrant and funny, warm and smart and strong, and they lived. That’s what has stayed with me after finishing the translation, and what I hope will stay with readers, too. Their aliveness.”

Berest, in the sections where fact and fiction come together, is reclaiming the stories of her family. She is also reclaiming her Jewish identity and heritage which will pass along to her children.

So why is this book so important today?

Berest and her mom are discussing why foreign Jews, such as the Rabinovitch family, were among the first to be deported. They didn’t have the support systems that the “French Jews” had and so they were vulnerable. “They existed in the gray area of indifference. Who would take offense if someone attacked the Rabinovitch family?” The Nazis and their collaborators pulled families apart, working systematically to put Jews into a “separate” category. Anne speaks directly to her mother in this discussion:

“Maman . . . there comes a point when you can’t just keep saying ‘but people didn’t know . . . Indifference is universal. Who are you indifferent toward today, right now? Ask yourself that (emphasis added).”

That paragraph reminded me of recent writings by Quaker activist Parker J. Palmer on ways we can fight the indifference to injustice and evil in today’s world.

We could bear witness . . . that our commitment to human rights, the rule of law, the claims of truth, and constitutional democracy demand that we resist a tyrannical regime that refuses to abide by those cherished norms.

In bearing witness to those trying to isolate us today, Palmer asks that we recall . . .

- that ICE is holding 65,000 immigrants in “detention,” working with a goal demanding at least 3,000 more detentions per day.

- Of the 65,000 men, women and children now in custody, 72% have zero felony convictions, only 7% are classified as serious criminal threats, and none has been afforded due process.

- We should also make it clear that immigrants—those who are being targeted—are NOT a major source of U.S. crime—in truth, they commit fewer crimes than U.S.-born citizens

- Congress has just funded a massive $150 billion expansion of our ability to catch, cage and disappear racially profiled human beings. (The budget for building new ICE detention centers alone is 62% larger than that of the federal prison system.)

- “These are your taxes and mine at work financing inhumanity and systematic injustice.”

The dear friend and former colleague who recommended The Postcard called it “painful at a profound level, of course, and yet somehow resilient and inspiring.” Well chosen words for a book that is both timeless and so necessary in today’s world.

More to come . . .

DJB

For further information, listen to this Scott Simon interview with author Anne Berest.

Photo of Auschwitz, Poland, World Heritage Site (credit UNESCO).

David, translator Tina Kover here. I can’t thank you enough for this beautiful and deeply thoughtful review.

Tina, you’re welcome. I found it so very moving . . . a book that will stay with me for a long time. Thank you for your work to bring this book alive to the English-speaking world. DJB

Tina, I wanted to pass along a note that my friend Judy (who has lived and traveled extensively in France through the years) sent my way. Judy originally recommended this book to me. I mentioned to her that you had made a very nice comment to the original post, and she wrote back with the following:

“Thanks so much for pointing out the translator’s comments—loved reading them as I had wondered how anyone could actually do this translation so impeccably. Did I tell you that after I read the book in English, I re-read it in French—figuring I could decipher what I didn’t understand in French just by having read the English translation….and it worked! The same heart and soul throughout every beautifully written page!! The translator succeeded in inhabiting the emotions fully!”

Tina, I thought that was very high praise and I wanted you to see it. DJB

Pingback: Observations from . . . August 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: August 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: What our books reveal about us | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Readers choice: The best of the 2025 MTC newsletter | MORE TO COME...