“Invitation to Participate: Sexual Practices in a Small Midwestern Town.” As subject lines went, it left a lot to be desired.

The reader might be as initially confused as the characters in this “thoroughly refreshing” work (Kirkus starred review). But thanks to the love, delight, and deep understanding of small town America that pours through the writing, one is quickly caught up in a series of linked stories that are less about sex and more about complex and complicated relationships in places where we least expect it.

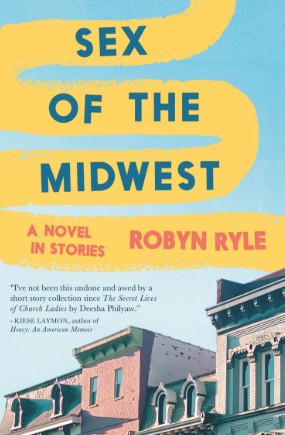

Sex of the Midwest: A Novel in Stories (2025) by Robyn Ryle begins as the residents of Lanier, Indiana (population 12,234) wake up to discover an email in their inbox inviting them to participate in a study of sexual practices. The town is soon abuzz (as small towns often are) trying to figure out how Lanier was chosen and who wrote the email. A legendary basketball coach is convinced the e-mail and the epidemic of STDs at the junior high are both part of the moral decline of the town, and although he has to drag around an oxygen tank he sets out for action. The bartender at the Main Street Bar finds that the email brings back fear of a midlife crisis. A town employee who likes to follow the rules is surprised to find where life’s pathway takes her after receiving the email. “Street by street and house by house, the e-mail opens up the secret (and not-so-secret) lives of one small town, and reveals the surprising complexity of sex (and life) in the Midwest.”

Sex of the Midwest, the first book of the independent Galiot Press, is a work to treasure. I first met Robyn many years ago when she spoke at a National Main Street conference. We’ve stayed in touch since then and I was delighted when she agreed to this chat for my Author Q&A series.

DJB: Robyn, some might see the title “Sex of the Midwest” and think they are getting a titillating romance novel, but your love in this book is really for small towns and the people who live in them. What is it about small towns that captures your heart and imagination, and how does that play out in your new book?

RR: I grew up in a small town, which I then escaped when I turned 18 and went away to college—a very familiar story. It took me a long time to realize the things I appreciated about growing up in that small town. The sense of being known and held. I was always Julia’s grandchild. Tom and Shirley’s daughter. Wendy’s sister. That can be stifling, but also very comforting.

When I moved to Madison (where I live now) I wasn’t intentionally choosing to live in a small town again. I moved for the job at the college up the road. But in Madison, I remembered all those things about small towns that I’d loved growing up, with the added bonus of not being from here, which made it much less stifling.

In Madison I realized that one of the advantages of living in a small town is the opportunity to learn a place deeply. Yes, a small town is never going to have the same diversity you get in a city, but you get the chance to find a different kind of diversity through intimacy with the lives of the people around you. It’s much harder in a small town to categorize or stereotype people. You know too much about them to reduce them to an over-simplified label. I love the way living in a small town can force you to confront the complexity of your neighbors. I think there’s something really beautiful about that. Maybe even a little sacred?

Which isn’t to say that there also isn’t a lot of small-town drama. Enough drama, in fact, to fill a book! But at the end of the day, we still have to live next to each other. So there’s more pressure to figure it out. There’s more incentive to keep doing the hard work of seeing each other as fellow human beings.

Reviewers have compared your work to “Olive Kitteridge,” “Spoon River Anthology,” and even Chaucer. (High praise indeed!) Did you first envision these as stand-alone pieces or were they always intended to be part of a larger novel-in-stories?

I tried as much as possible when I started the first story (which was “Don Blankman Saves the Youth of America”) to not really define what I was doing—whether it was a novel or a short story collection. I find it much easier to write short stories. They’re so neatly self-contained compared to the unruliness of a novel. I’d tried to write many novels with what I felt like was limited success. So I just started writing without really making a decision about where I would end up. I had to trick myself a bit, so to speak.

Because they were stories about a small town, it made sense that people would keep reappearing. And gradually, trajectories for the characters began to emerge. After I had most of the stories written and had edited them a few times, I thought about making it more novel-ish. I thought about leaning toward a more traditional novel structure. But it felt forced. And certain stories would probably have had to go (like “Return” which introduces a new character well into the narrative). Also I was reading more books that ignored the line between short story collection and novel (like Jonathan Escoferry’s If I Survive You) so it seemed like it might be possible to do that, too.

The pandemic and its aftermath as well as the political divides in this country play supporting roles in “Sex of the Midwest.” One character―a grouchy former basketball coach―refuses to get vaccinated, comes down with Covid, and now needs a new lung. He’s also on a crusade to save the youth of Lanier from sex while carrying on his own long-time affair. Older residents have to navigate newcomers, gentrification, and change. Loneliness and the search for connection and community pop up frequently. What was it in these storylines―and how they play out in small towns―that captured your imagination and led you to share them with your readers?

I started the stories in late 2022, which was a time when I felt like I had a little distance from both the pandemic and the first Trump presidency. I had a little breathing room and I was very tired of being angry. I wanted to try something different. I wanted to put myself imaginatively into the mind and heart of someone who didn’t think like me at all. It was my coping strategy. I still do it sometimes when I’m just totally baffled by something or someone in the world. I put a version of that person in a story and see what happens. It’s very hard to hate someone once you really try to see the world from their point of view. You can definitely still disagree with them, but probably not hate them.

I also realized that the experience of the pandemic I had in my small Indiana town was very, very different from how people experienced the pandemic in New York or Boston or Chicago. I wanted to tell that story.

In my writing, I’m almost always trying to push against over-simplified, stereotyped narratives of small town life and rural places and flyover states. There’s a lot of anger in rural America about the way we get depicted in the media and the assumptions people make about us. I think that anger makes sense, even if gets directed and channeled in dangerous ways. National media only show up in towns like ours when there’s a disaster—a tornado, a flood, or a mass shooting. But we have interesting stories, too. Our lives are also complex and complicated in ways that are important.

If you know New York, you don’t know all big cities. Each city is unique. The same is true of small towns and I wanted to tell one unique story about one unique place.

The bartender Rachel Barr discovers that she has a gift for writing stories about her observations, and in that way she seems your alter ego. Were there characters who really spoke to you and conversely, were there characters who were more difficult to bring to life?

Clearly, I think Don Blankman as a character jumps off the page. There were things about writing in his voice that were fun, but there were also moments when I did not want to be inside his head one moment longer. I love Don, but I wouldn’t want to spend a lot of time hanging out with him. He was a difficult character to write because on the one hand, I didn’t want people to think that I agreed with many of Don’s beliefs. On the other hand, I didn’t want readers to feel like I was making fun of him, which was not at all my intention. I have great hope for Don. I believe that in writing and making art, we are trying to create the world we want to live in. So I try to be hopeful about Don and his capacity for change.

Yes, Rachel is a writer and, like me, she has some complicated feelings about the whole idea of writing workshops. There is, in fact, a Virginia Woolf Room at the Sylvia Beach Hotel in Newport, Oregon, and I have stayed there, though, unlike Rachel, I did not have a breakdown that involved a duck. I put a lot of my thoughts and feelings into Rachel, but also into Loretta and Joyce and James and Sam and Nancy and even Don. It’s the great thing about writing. You can take all your thoughts—even the weirdest ones—and put them into other people’s heads and no one knows which ones are yours or not.

Do small towns have lessons for the rest of the country?

I think small towns do have a lesson for the rest of the country. I think the loss of community is part of how we got to this very frightening place we’re in right now as a country. I think small towns can remind us how to live together, here, in this actual physical world, rather than in the cruel and terrifying spaces of social media and the internet and the news.

It is so, so hard in our current historical moment to hold on to the full humanity of the people around us. There is so much dehumanization going on. I’m guilty of this myself, even as I’m consciously aware of trying not to. I’m not saying that it’s impossible to dehumanize each other in a small town, but I think the proximity and the intimacy make it a little harder. To see your neighbors as fully human certainly makes life more pleasant.

My husband and I are academics and on our small campus, we have to line up several times a year for formal ceremonies like graduation or honors convocation. We stand around in what we call the line of march, often for 20-30 minutes before the ceremony starts. So a saying my husband and I have is, “Never have someone you can’t stand next to in the line of march.” Which is a way of saying, never create a situation where you can’t at least chit-chat with someone for 20 minutes or so. You don’t have to want to be their best friend. You don’t have to agree with them about everything. But make sure you can be civil, even if it’s only twice a year.

The same applies to a small town. Never have someone you can’t stand in line at the coffee shop with. That seems very small, but that basic civility is what allows us to trust that we are all humans with largely good intentions. That civility might eventually lead us to areas of commonality. It might lead us into conversations and compromise and understanding and, you know, community. Which isn’t at all an easy thing, but, I think, is a big part of what we’re on this planet do do.

Thank you, Robyn.

It was such a pleasure to talk to someone who really understood the book and what it’s all about. Thanks for doing this.

More to come . . .

DJB

UPDATE: Robyn was interviewed on NPR’s Weekend Edition by Scott Simon, and she “was smart and funny and thoughtful, and she had a great and important message to share.” Recommended!

For other chats in my Author Q&A series, click here.

Photo by MATHEW RUPP on Unsplash

I’ll have to get this one. Sound good.

I think you’ll find a lot in it that resonates, Kathy.

Pingback: Observations from . . . September 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: September 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . October 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Pull up a chair and let’s talk | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: What our books reveal about us | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Readers choice: The best of the 2025 MTC newsletter | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Disengage with your misery machine: Vol. II | MORE TO COME...