Essays to celebrate movement at a human pace. Movement that fosters encounters, discovery, and surprise. In the latest installment of the Author Q&A series, editor Ann de Forest chats with me about her book on the ways of walking.

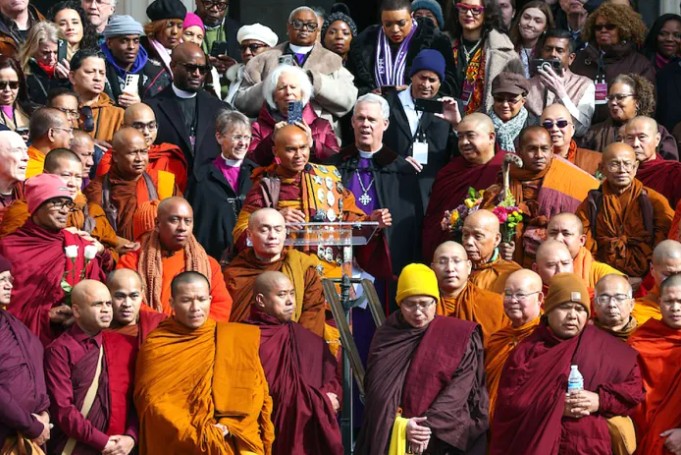

Last week nineteen monks from the Huong Dao Vipassana Bhavana Center in Fort Worth arrived in Washington. Gathering at the Washington National Cathedral for a “sacred stop” with faith leaders from a variety of traditions, they were nearing the conclusion of a 108-day, 2,300-mile journey on foot from Texas to the nation’s capital. The Walk for Peace was designed to raise “awareness of peace, loving-kindness and compassion across America and the world.” It also raised awareness about the power of the simple act of lifting a foot, swinging a hip, bending a knee to plant that foot on solid ground, and then repeating those actions over and over again.

As the monks were arriving in the nation’s capital I was completing a recent book of essays from writers who amble, zip, stride, stumble, and march. Who walk slant and walk slow. In an age that prizes speed and efficiency, these writers—like the Buddhist monks—are moving at a human pace in ways that foster encounters, discovery, and surprise. These essays invite you to read them at a leisurely pace, taking the time to ponder life’s questions.

Ways of Walking (2022) edited by Ann de Forest is a collection of 26 wide-ranging essays whose writers reflect on where they have walked and what they have discovered. Exuberant, troubled, surprised, and reflective—often as part of the same journey—these authors are always thoughtful and observant. They grapple with a multitude of questions, the most basic one being, “Why did you start to walk?” Once one makes the decision to reach out and grab life, walking at a human pace is a decision to encounter it intimately. Edward Abbey famously said, “Life is already too short to waste on speed…. Walking makes the world much bigger and therefore more interesting. You have time to observe the details.” It is a sentiment shared by many of the authors of these essays. And in their walking, these writers are sometimes crossing forbidden lines and breaking boundaries. Some are walking—like the monks—for social justice and peace. Others are pushing themselves to deeply explore their immediate environment in order to understand the challenges to our lives on this planet. Throughout there are discoveries, both small and large.

Matthew Beaumont described Ways of Walking as “a moving, endlessly stimulating invitation to walk, to think, and to rethink walking.” I was delighted when the book’s editor, Ann de Forest, agreed to chat with me in this newest installment of my Author Q&A series.

DJB: Ann, why is walking often seen as a subversive act?

AdF: For so many reasons. Walking counters much of what we’re told to prize in contemporary society. In an age of speed and efficiency, walking is slow. Walking favors process over product, and fosters attention in a culture that feeds on constant distraction. Walking tears us away from our screens and thrusts us into the material, physical world, which we encounter with our actual, physical bodies. Which then makes us realize our own bodies’ power to move independently—no need for special equipment or training or education. Walking is also a great leveler. Nearly every other human being on this planet also walks. Walking is our human heritage, linking us with those who’ve come before us and those who will come after us. And in our current divisive climate, that sense of connection that walking fosters can be seen as subversive as well.

Visionary peacemakers like Gandhi and Martin Luther King understood walking as an empowering form of civil disobedience, a counter against violence and hatred, a means of fostering unity instead of division. Like many, I’ve been moved by the Buddhist monks who just completed a 2,300 mile walk for peace across America, demonstrating by their steady, deliberate witness that there is an antidote to our country’s current frenetic, destructive pace.

You write about growing up in Los Angeles where the common perception is that nobody walks. Yet you did, even walking the length of Ventura Boulevard with a high school friend. What did you learn about yourself, Los Angeles, and the act of walking from these perambulations around the city?

I wouldn’t have been able to articulate this as a kid, but there’s an absurdity about L.A. that, I think, exposes the inherent absurdity of every city, and maybe every built environment. I say that with the greatest affection for my hometown. Growing up there I accepted as normal the jumble of contradictory architectural styles, the dizzying shifts in scale, the blurry co-existence of suburban, urban, rural, and industrial spaces, and somehow understood how tentative and temporary the whole assembly seemed. Walking in the city, especially as a teenager, felt like a small rebellion, but at the same time an eccentricity in tune with this already eccentric place. Walking along a car-centric corridor like Ventura Boulevard taught me to notice the city’s seams, to consider more closely the parts that contributed to the motley assembly, which led to a deeper appreciation for the history of the place. Ventura Boulevard, for instance, revealed itself as a linear quilt of small-town Main Streets stitched together into a major thoroughfare. I had yet to hear the term “urban fabric,” but one of the things I learned about myself is that I liked exploring and discovering hidden histories of place, and the decisions that went into forming places. And when I became a writer, the resonance of place became my central theme.

Walking in L.A., because it was eccentric, made my friends and me feel like we were privy to secrets nobody else knew about. Wherever I walk today, I still have a habit of poking around corners and back alleys, always on the lookout for small surprises that drivers would never see. Tom Zoellner’s essay about walking out of LAX captures that spirit so well. On a whim, he decided to walk the seven miles from the airport to his home in Venice Beach and along the way stumbles upon hidden pockets of community life and greenery tucked in between the concrete and asphalt infrastructure that in a car would have been his path home.

Lena Popkin’s essay “Travel Lightly” describes the different perspectives that a man and a woman bring to the same walk, even at the same time. Women, especially single women walking alone, can experience a fear that someone like me―walking out of a space of straight, white, male privilege―may never experience. She writes that walking has taught her both real danger and real peace. How did some of the other writers in this collection respond to her call for us to hold multiple truths in one space?

Lena Popkin’s realization is so wise. It takes most of us years to trust our capacity to hold two, or more, contradictory thoughts or emotions at once—and she was my youngest contributor. Several of the writers deal with similar contradictions, and your question makes me reflect on whether the act of walking helps us expand our capacity for holding—and possibly reconciling—multiple truths. I think of Hannah Judd walking aimlessly along the Chicago lakefront in the dark mourning her father after his sudden, unexpected death, while holding a joyous and consoling memory of the time they walked together across the Brooklyn Bridge, a walk she had surprised him with as a birthday present. I think of Ruth Knafo Sutton’s father holding two different, beloved places in his mind at once, a bend in a river in Allentown, Pennsylvania reminding him, every time he encounters it, of his boyhood home in Morocco. Nostalgia for a place he’s lost co-exists with the joy of meeting its mirror in his present life, walking with his daughter in his old age.

When we walk, we often experience what could be called a cognitive dissonance—between our freewheeling minds and our physically taxed bodies, or between the sheer pleasure of moving and the harshness of our surroundings. But somehow walking makes these contradictions feel more harmonious than dissonant. Adrienne Mackey, in her essay “(while walking),” conveys the mental and emotional drifts, the exhilaration and physical pain that occur on a 5 ½ day, 103-mile trek around the entire perimeter of Philadelphia (a project which I was involved in as well, and that indirectly inspired this book). “It is raining and I am soaked and I am walking on a high bridge that brings out a small fear of heights,” she writes. When a companion says, “’This is fun,’” she looks out over the oil refinery wasteland below and tries to see it as beautiful. “This is fun,” she decides. “Anything can be fun if you simply shift your perspective.”

Walking doesn’t always involve putting one foot in front of the other. Victoria Reynolds Farmer writes about traversing the City of London in a rented wheelchair. What perspectives and truths came out of her experience that were especially meaningful to you, as the collection’s editor?

Victoria’s deeply resonant essay offers yet another example of someone capable of holding multiple truths at once. As soon as I started assembling this collection, I knew it was essential to include perspectives from those for whom walking presents challenges and risks. Victoria, who was born with cerebral palsy, writes about a trip to London, a place she’s long dreamed of, where she imagines herself walking in the footsteps of one of her literary idols and inspirations, Virginia Woolf. She immediately encounters obstacles. As a city bus passes her by because it only has space for one passenger in a wheelchair, she realizes she can never move through London like Virginia Woolf, absorbing its boisterous energy. And if she had dwelled on that moment of dashed dreams, hers would have been a fine essay, rousing readers’ indignation over the injustices of an infrastructure designed solely for the able bodied.

But Victoria’s dashed dreams lead her—and her readers—to a more profound place. There are sentences that break my heart like this: “… in the middle of a city I had loved for so long, a city that didn’t seem built for my existence in the world, I began to think deeply and intently about my life inside my body.” Hers is a spiritual journey. Every time I read her essay, I feel the poignancy of her disappointment as my own, and not just because she is a gifted writer who helps her readers share her experience through both her mind and body. It’s because she taps into a feeling most of us can relate to—the disappointment when a desired ideal doesn’t match the reality. She articulates a quintessentially human paradox: we exist as bodies, flawed, vulnerable, often weak, and certainly mortal, and yet also exist as spirit, on a loftier, limitless plane. The truth that resonates for me is that it’s in the gap between our exalted ideals and our physical brokenness where we are the most human.

Finally, Ann, more than one writer references the stories that go together to make the places we walk. However, multiple writers also discuss the fact that people and places are disremembered as cities, towns, and landscapes grow, shrink, and change. Do you see answers in these essays about how we can walk and see what has deliberately and sometimes violently been unseen?

This goes back to your first question about why walking can be considered a subversive act. Walking can be a profound act of both witnessing and reckoning. This summer I heard a presentation by artist Kamau Ware, who runs immersive Black history tours in Lower Manhattan. He said several times that the goal of his project was to make people “remember,” and it struck me as he was talking that one opposite of “remember” could be “dismember.” In other words, we need to re-member all the broken, fragmented, and buried lives and stories in order to make ourselves, the spaces we live in and move through, and our society truly whole. Of course, one has to first know what histories have been erased or suppressed in order to acknowledge them. Jee Yeun Lee, who walked 100 miles along arterial roads radiating from downtown Chicago, did extensive research before she set out; her narration functions as a palimpsest where stories of broken treaties, forced displacement, environmental degradation, and genocide emerge beneath the contemporary surfaces of upscale shopping districts, shipyards, strip malls, apartment buildings, and suburban neighborhoods. She describes her work as an attempt to “decolonize” the American landscape.

Walking with intention, as a kind of ritual or performance, is another way of not just reconciling with the painful past, but acknowledging our own complicity. I love the way Nathaniel Popkin describes his movements on a penitential walk to follow the trail of the infamous Walking Purchase, one of the most shameful land swindles in American history. He wanted to to “unzip” and “zip” and “unzip” again. For me, the answer to your question is in those words. The unzipping is a means to open and expose, while the zipping carries healing and reconciliation. We can’t heal wounds without first acknowledging that they exist. We can’t remember without being aware of the acts of dismemberment. Remembering, like walking, is an ongoing act. There’s always more unzipping to do. Especially right now, when our government is on a mission of suppression and erasure!

Thank you, Ann.

It’s been a pleasure.

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo of Walk for Peace from Wikimedia

Pingback: Observations from . . . February 2026 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: February 2026 | MORE TO COME...