As the late fall weather arrives in Washington and the leaves cover the ground, my thoughts have turned to one of the best natural history/science books I’ve read in years.

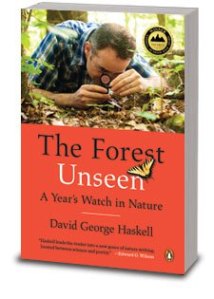

The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature by David George Haskell is both very modern and very old fashioned in its outlook. Haskell’s work is a meditation of a year’s worth of observation on a small patch of old growth forest — which he refers to as his mandala — near Sewanee, Tennessee.

Every few days Haskell visits this patch of land and captures his observations. The chapter for December 3rd is entitled “Litter,” as the forest floor is covered with leaves and other dying plants, similar to what we see along the C&O Canal, Rock Creek, or Sligo Creek here in Washington. The first half of the chapter is an explanation of the leaves, mushrooms, bugs, seeds, fungal strands, and the unseen microbial community in the soil of his mandala. But after noting that ecological science has yet to fully digest the discovery of the belowground network – as we still think of the forest as being ruled by relentless competition for light and nutrients – Haskell closes with a series of paragraphs that speak to the importance of cooperative action and roots.

“We need a new metaphor for the forest, one that helps us visualize plants both sharing and competing. Perhaps the world of human ideas is the closest parallel: thinkers are engaged in a personal struggle for wisdom, and sometimes fame, but they do so by feeding from a pool of shared resources that they enrich by their own work…Our minds are like trees — they are stunted if grown without the nourishing fungus of culture.”

Haskell speaks to the fact that “evolution’s engine is fired by genetic self-interest, but this manifests itself in cooperative action as well as solo selfishness.” And he wonders if his new ways of thinking about evolution and ecology are so new after all.

“Perhaps soil scientists are rediscovering and extending what our culture already knows and has embedded into our language. The more we learn about the life of the soil, the more apt our language’s symbols become: ‘roots,’ ‘groundedness.’ These words reflect not only a physical connection to place, but reciprocity with the environment, mutual dependence with other members of the community, and the positive effects of roots on the rest of their home. All these relationships are embedded in a history so deep that individuality has started to dissolve and uprootedness is impossible.”

Haskell’s work over his year in the forest is an attempt to “put down scientific tools and to listen: to come to nature without a hypothesis, without a scheme for data extraction, with a lesson plan to convey answers to students, without machines and probes.” Listening moves us all past what we know and into the deeper knowledge to be found when we tap into the roots of nature and humanity.

Have a great week.

More to come…

DJB

Image of Sligo Creek Bridge by DJB

Thanks for another recommendation that helps us reflect and appreciate out world and life.

Best, Deedy Bumgardner

Thanks, Deedy. I appreciate the feedback and – more importantly – I appreciate your taking the time to read these posts. All the best. DJB

Pingback: The Flip Side of Ignorance | More to Come...

Pingback: Eleven Ways of Smelling a Tree | More to Come...

Pingback: Our entangled life | More to Come...

Pingback: The hidden life of trees | More to Come...

Pingback: The past and future of one weird rodent | More to Come...

Pingback: Wood that rejoices in transmitting music | More to Come...

Pingback: The networks that sustain and shape us | More to Come...

Pingback: The earth is our home | MORE TO COME...