While traveling with new and long-time friends on a recent National Trust Tour in Panama and Costa Rica, I shared observations on how we engage with the past and old places. Both lectures were built around the premise that the reason older places matter is not so much about the past or only about the past. These places matter to people today and in the future.

We create a narrative out of our lives to make them meaningful and coherent, and I wove this into the context of our trip through the Canal, into the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Old Panama, and as we explored San José and other parts of Costa Rica. Memory, identity, and continuity are all part of the narratives — the pathways — of our lives. They are also fundamental reasons why old places matter.

Memory

History often comes from perspectives shaped by our memories. Perspective is a point of view . . . not the whole view. “Memory is a poet, not a historian” suggests Marie Howe.

Memories fade with time and they change as others share the story of the same event. Points get lost — or found — in translation. What begins as metaphor ends up being repeated as fact.

Yet memory is an essential part of consciousness and so many memories are tied to places. Memories are shaped and reshaped in thousands of ways we seldom recognize or acknowledge. All of which suggests that there will be differences in how we see the places we visit.

We have generally chosen to save that which reflects well on us — beautiful buildings and sites that uplift. One of the challenges we face in the U.S. and in Latin America is to find ways to preserve and interpret sites that tell the stories of those who have traditionally been marginalized and not part of the long-told narrative, places where the story and the intangible and hidden history are just as important, if not more so, than the architecture.

Places of all types are important in how we understand our past as they key both individual and collective memories. We may have individual memories related to baptisms, bar and bat mitzvahs, weddings, and funerals in a specific religious site, but those we visited on the tour also spark collective memories, both for residents and for those of us who visit.

Why are memories of the Embera community, visited by some of us on the pre-tour, important? Those memories and places tell us something about ourselves as humans. They may spur thoughts about the longevity of the human race or the importance of different relationships to the earth. The resilience this community has exhibited over millennia can inspire us today.

There is no road, not even a primitive one, across the Darién where the Embera live. “The “Gap” interrupts the Pan-American Highway where some 66 miles has never been built. We had to access it by canoe. But it was a trip well worth making.

Old places give us a chance to feel a connection to the broad community of human experience.

Identity

We often talk in language that recognizes the crucial connection between identity and old places. In the ancient world, Seneca phrased it as, “No man loves his city because it is great, but because it is his.”

Buildings, and neighborhoods, and nations are insinuated into us by life. Think of the way we may be linked, directly or through symbolic forms that tie people and land together, such as links through history or family lineage. And then there are “universal links through religion, myth and spirituality, links through festive cultural events, and finally narrative links through storytelling or place naming.”

Old places also embody our civic, state, national, and universal identity. In the U.S. we speak of American exceptionalism. But citizens of other countries also hear that their homeland possesses desirable qualities that others lack. French nationalists “tout the elegance and sophistication of their ‘civilization,'” while Serbians “have traditionally considered themselves the shield of Christianity.”

We heard of Costa Rica “exceptionalism” from our tour guides. “Costa Rica is different” they would say.

As with most countries, it is complicated.

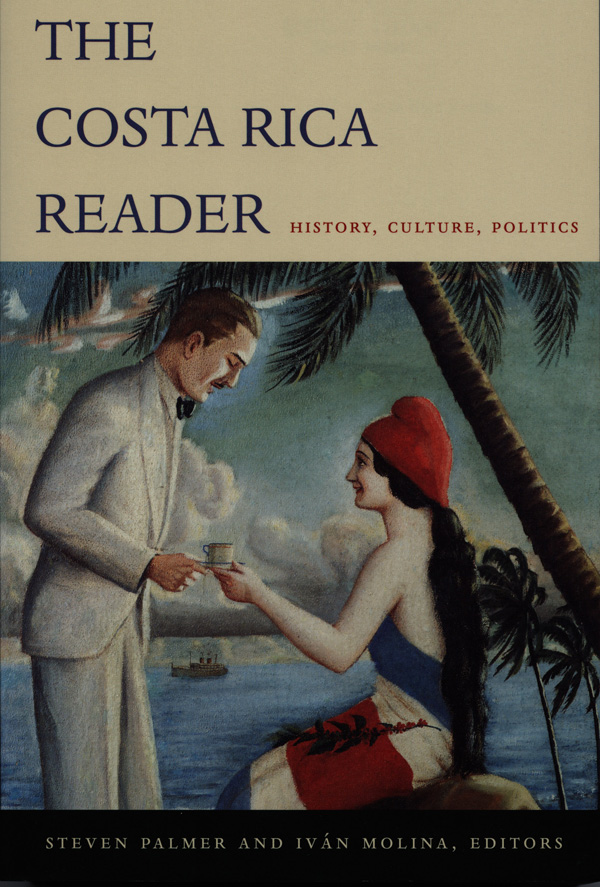

The Costa Rica Reader: History, Culture, Politics (2004) edited by Steven Palmer and Iván Molina expands the perspectives around this intriguing Latin American nation by bringing new voices to the conversation. “Exceptionalism” is a term often used to describe Costa Rica, which is seen as “different from other Latin America countries.” It has never been consumed by civil strife or race-based oppression, the story goes, and it is the only country to have enjoyed uninterrupted political democracy for three-quarters of a century. Yet as Palmer and Molina write, some observers suggest that exceptionalism is at the center of a dubious mythology. This work is composed of short pieces that give a much fuller understanding of Costa Rica, showing it “as a place of alternatives and possibilities that undermine stereotypes about the region’s history and call into question the idea that current dilemmas facing Latin America are inevitable or insoluble.”

National identity is important, but we can resist the temptation to “see the country as an exception” while insisting “on the distinctiveness of its past and present.”

Continuity

In a world that is constantly changing, old places provide people with a sense of being part of a continuum — a necessity to psychological and emotional health, connecting us over time and space.

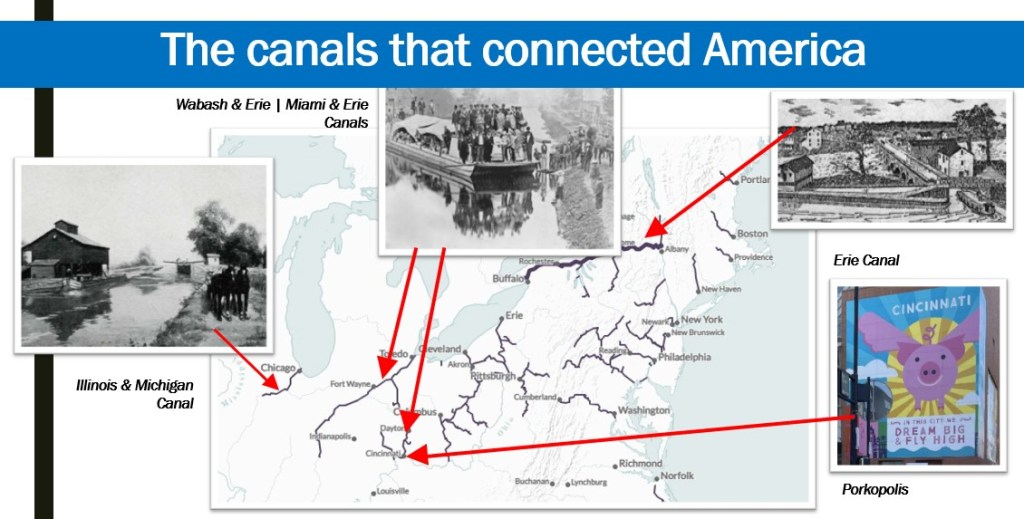

A key part of the continuity of canals that many don’t readily see is the vast network that sprang up in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. While the heyday of the canals lasted only a few decades, they transformed the American economy by connecting the areas west of the Appalachian Mountains to eastern population centers and Atlantic ports. Concentrated largely north of the Mason-Dixon line, they shaped American regionalism by linking the northeast and northwest together into a region that increasingly came to see itself as the “North.”

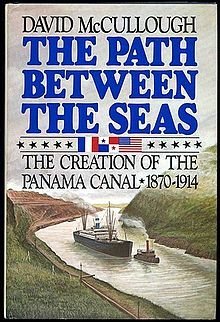

Applying his remarkable gift for “writing lucid, lively exposition,” David McCullough “weaves the many strands” of the momentous building of the Panama Canal “into a comprehensive and captivating tale.”

I last read The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (1977) by David McCullough several decades ago. But I picked it out of my bookcase and reviewed David’s work prior to this trip, as it is the indispensable work that “tells the story of the men and women who fought against all odds to fulfill the 400-year-old dream of constructing an aquatic passageway between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It is a story of astonishing engineering feats, tremendous medical accomplishments, political power plays, heroic successes, and tragic failures.”

We saw this marvel up-close as we sailed under the 2019 Puente Atlántico — the Atlantic Bridge — entered the canal and moved through the locks over the better part of a Sunday, rising first to reach the level of the massive man-made lake in the center of the isthmus that makes this canal work on many fronts before being lowered back down again to sea level on the Pacific side.

McCullough spends time in his book talking about the color line that cut through almost every facet of daily life in the Panama Canal Zone during construction. It was clearly drawn and as closely observed as anywhere in the Deep South during that period.

Black West Indians and white North Americans “not only stood in different lines when the pay train arrived, but at the post office and the commissary. There were black wards in the hospitals and black schools. White workers had living quarters while the Black West Indians had 50 X 30-foot rooms that slept 72 men . . . or they had none at all.

David — a long-standing National Trust Trustee Emeritus before he passed away — wrote that it was debatable if the West Indians working in Panama were better or worse off than a Kentucky coal miner or an immigrant mill hand in Homestead, Pennsylvania. They did get free medical care and ate very well. It’s just that the working classes at the turn of the 20th century were expendable, conditions which led to major changes throughout that century.

As we marveled at the engineering wonder of the Panama Canal it was important to remember that this particular pathway between the seas is just part of a much larger pathway of continuity, connecting our past, present, and future, with all of its glory and with all of its challenging history.

And more!

Several days were devoted to wildlife viewing along the coasts and in Costa Rica’s parks, including the wonder-filled Manuel Antonio National Park.

All-in-all a fascinating ten days and yes, just another wonderful National Trust Tour.

Join us for a future trip!

More to come . . .

DJB

The Weekly Reader links to the works of other writers I’ve enjoyed. I hope you find something that makes you laugh, think, or cry.

All photos by DJB unless otherwise noted.

We have taken many National Trust tours in the past . They are wonderful and you meet the nicest people . We met you on one of them and also became friends with Grace Gary on another . Unfortunately traveling is no longer easy .

Nancy, that Black Sea trip where I met you and Donald remains among my most important memories. I really enjoyed the people on that trip (I also met my friends Ed and Ruth Quattlebaum there), and seeing those iconic places, especially given all that’s going on in the region now. We’ve always appreciated your support for National Trust Tours and miss seeing the two of you. Thanks for your note bringing back wonderful memories. All the best – DJB

Pingback: From the bookshelf: February 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . March 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Exploring places that matter | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Our year in photos – 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...