The Jewish German philosopher Walter Benjamin famously said that cultural treasures “owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents that have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries.” In his Thesis on the Philosophy of History, Benjamin wrote that “It is more arduous to honor the memory of anonymous beings than that of the renowned. The construction of history is consecrated to the memory of the nameless.”

Places of all types are important in how we understand our past, as they key both individual and collective memories. Sacred spaces—such as the churches, cathedrals, monasteries, and synagogues seen on our recent trips to Europe—are especially important in exemplifying both the beauty and challenges of landmarks. At home and around the globe we have generally chosen to save that which reflects well on us—beautiful buildings and sites that uplift. But among the challenges we face is how to tell the stories of the craftspeople and workers who made those places possible but who have not been part of the traditional narrative. Because religious institutions are at least in part human constructs, they are fallible with many sordid chapters in their history. How do we interpret these sites to include stories of those who have traditionally been marginalized?

Consecrated to the memory of the nameless

My friend and former colleague Adrian Scott Fine recently wrote that when we study places with difficult histories, “how we choose to either confront, understand, and re-contextualize a dark complicated past or erase and ignore what these places can do to teach us and those that follow” is important. Memory and identity are often disputed. Places, however, can transcend specific interpretation. Each of us will have different interpretations of the things we see, but the continued existence of the place permits the revision, reevaluation, and reinterpretation of memories over time.

Too many places that we’ve saved have not recognized the people who built them. That’s true for Irish, German, Eastern European, and Asian immigrants at a host of places across the U.S.

We are only now beginning to tell the fuller story of how the enslaved built many of the monuments in the U.S. and Europe, not to mention that their labor built our economies. With its long history of war, Europe has many churches where the clerics and leaders of certain periods supported governments in their actions to divide, ostracize, and even kill people who were designated as “others.”

Our identity—both personal and civic—is transformed over time. By preserving these places we can acknowledge the deeper, layered history and appreciate the continuous critical revision of identity informed by the past. There is much to celebrate in these landmarks of Europe. There is also much left out of traditional narratives that needs to be rediscovered and included. With that broader perspective in mind, I want to share some of the images from our recent trip while celebrating the unnamed craftspeople who made them possible and honoring the memory of those whose lives were harmed by actions of institutions that often acted as more of a secular state than as a place of religious refuge.

First views

I’ve long been intrigued by the first glimpse one catches of a church, cathedral, or monastery while moving through a historic city. When seen down a narrow street as in Strasbourg, some only hint at the grandeur to come. The scale may open up more fully as one moves to a main artery. These landmarks coexist with the cityscape even as they tower over it.

Others, as in Basel, are sited on a large plaza where their place in the community—at least at the time of construction—was clear. Or, as in Cochem, Germany, they help frame these public squares.

First sightings are often from a river, lake, or other body of water, such as the Rhine River in France and Germany. Here these sacred spaces might suggest a place of stability as one is carried along by the current of the river . . . or life.

Others are more isolated, glimpsed across a vineyard or forest, as with the Abbey of St. Hildegard in Rudesheim, Germany. Founded by Hildegard von Bingen in 1165, this community of Benedictine nuns was dissolved in 1804 but was then restored with new buildings a century later.

Resilience

Virtually every sacred landmark seen on this trip had been severely damaged at some point in time, often from war. In Strasbourg, the cathedral was bombarded during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, while during World War II, the Cologne Cathedral was the only major building not destroyed by bombing raids, as it was used by Allied pilots to target the rest of the city.

In Cochem, St. Martin’s is a major religious landmark. It has a long history and is dedicated to the city’s saint patron. The church, along with the rest of the city, was extensively bombed by the Allies during World War II. The church, including its iconic bell tower was rebuilt, and in an act of reconciliation eight stained-glass windows by British artist Graham Jones were installed in 2009. These gems look like watercolors and they reflect the colors of Cochem’s lush natural surroundings.

Exquisite craftsmanship on exteriors . . .

The craftsmanship is often what first attracts us to these landmarks.

. . . and on the interiors

We were in Amsterdam on this trip, but our visit to the city’s beautiful and historic Portuguese Synagogue actually took place last April. Nonetheless, it deserves a mention in this overview of sacred spaces in Switzerland, France, Germany, and The Netherlands.

Music

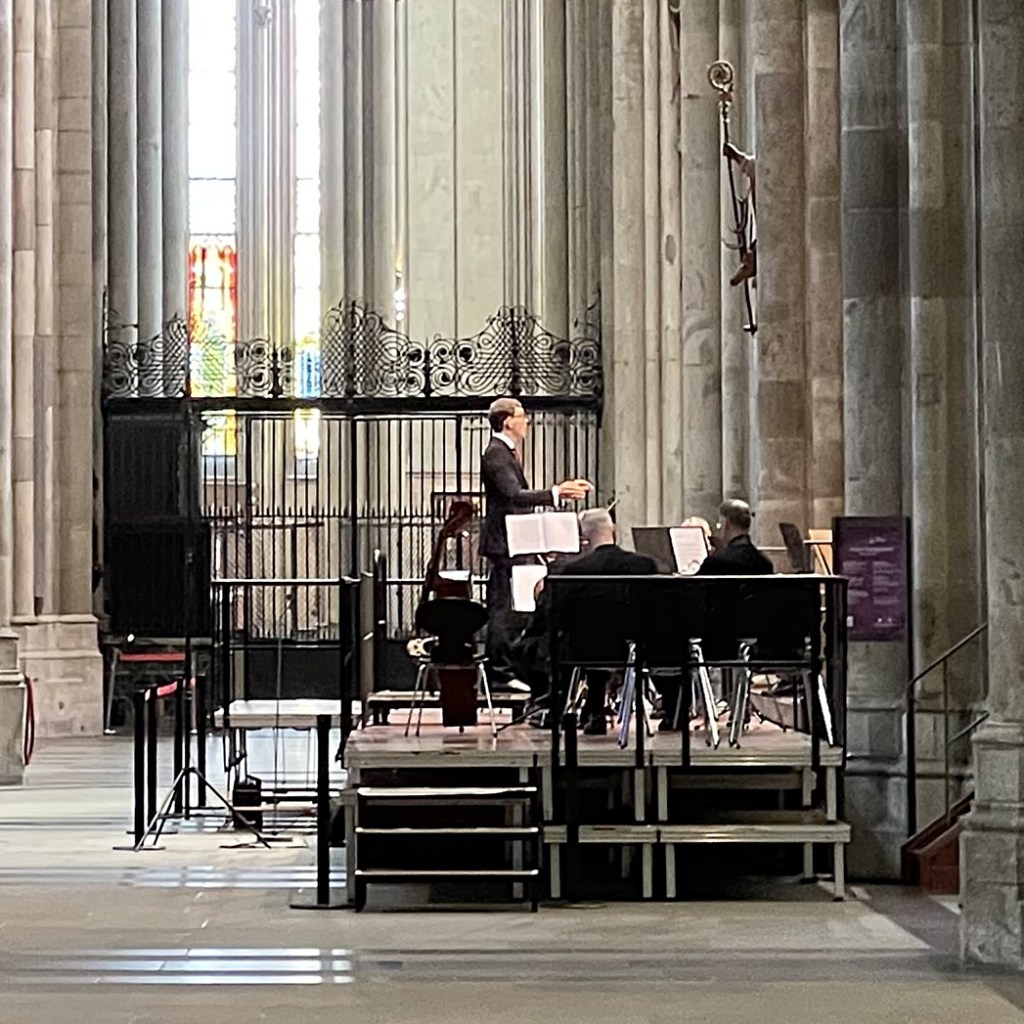

Several times on this trip we happened upon music while touring these beautiful spaces. In Cologne we arrived on Pentecost Monday in the midst of a mass with the Cardinal, an orchestra, and choir.

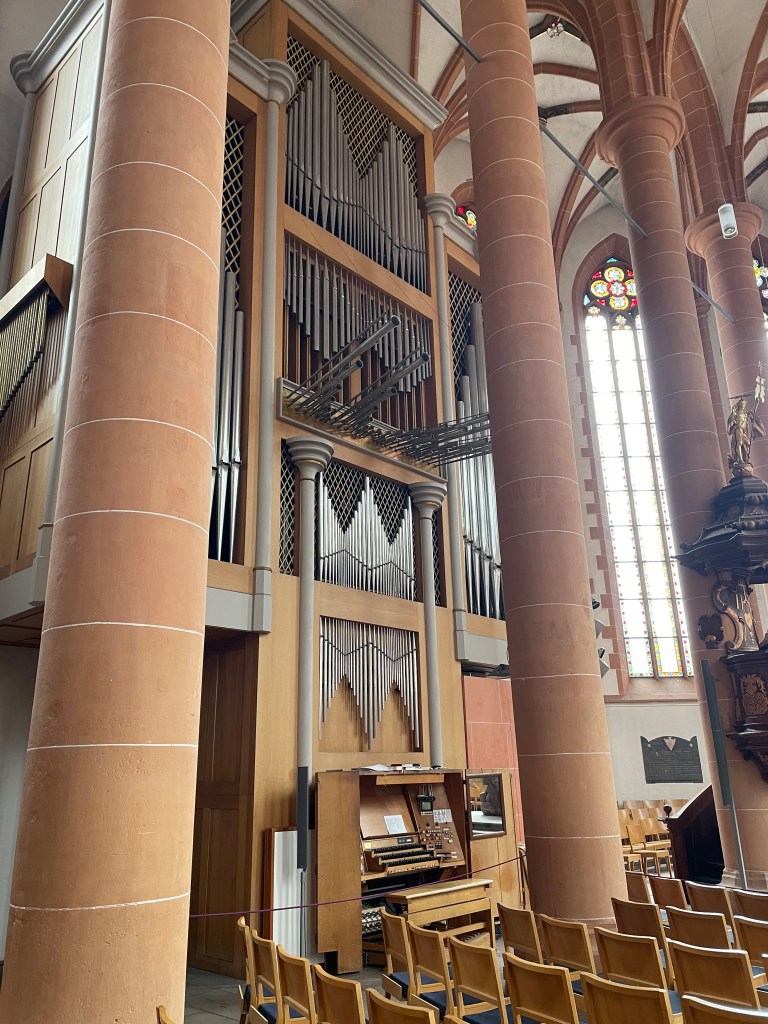

In Engelberg we lifted our hearts as the monks’ singing of Vespers washed over us at the end of the day. On that occasion and throughout our trip we saw, and sometimes heard, magnificent and beautiful organs, both historic and modern.

And we also visited the home city of one of the church’s most well-known composers: Hildegard von Bingen.

“In the Middle Ages, she was regarded as the herald of the approaching end of the world. The humanists celebrated Hildegard as the first great woman in literary history. During the Reformation, Hildegard was often invoked because she had used drastic words to complain about abuses in the papal church. Based on some miracle stories, the Romantics created the image of the “popular saint Hildegard”. Since the industrial age, holistic “Hildegard medicine” has become popular as a gentle alternative to apparatus medicine. Today, Hildegard is regarded by many as a pioneer for the emancipation of women. As the most important composer in the history of music, she is known above all in the USA, Australia and Japan. Hildegard’s holistic view of creation gives us valuable orientation in dealing with climate change. And in 2012, the visionary from Bingen was elevated to the status of Doctor of the Catholic Church on the basis of her extensive work—the fourth woman worldwide in 2000 years.”

Bingen Museum am Strom

As we were passing through vineyards in this land of Riesling, we drove by the community of nuns that she founded and that continues her work today.

Understanding that the identity and our understanding of Hildegard—like the sacred places we visited throughout this trip—is still “strongly overlaid by the ideas, myths and legends of past centuries,” it seems appropriate to end this meditation with the music of a prophetess who has fascinated millions for more than 800 years.

More to come . . .

DJB

Nighttime image of Cologne Cathedral by Nikolay Kovalenko on Unsplash. All other photos by DJB unless otherwise credited.

Pingback: Our journey through Europe | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . June 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Oh, the places we’ve seen! | MORE TO COME...