The fascinating and engaging story of how one of the most famous celebrities of her time became a French spy during World War II.

Before the Second World War she was known as “the Black Venus.”

Born in St. Louis, she grew up during the age of segregation. At 15 she had already been married twice. She was working full-time as a servant, resorting to rifling through public bins for scraps of food to survive.

Yet she could dance. In 1921 she was cast in an early all-Black musical on Broadway. Four years later she won a place in a Paris show, La Revue Nègre that paid her $1,000 a month. With that break Josephine Baker set sail for France. As the world’s first female superstar of color she danced the Charleston “dressed in nothing but pearls and a banana skirt, parading her pet cheetah.” Her act scandalized and delighted le Tout-Paris.

By 1939, as war was enveloping Europe and her beloved Paris, Baker was Europe’s highest paid entertainer and one of its best-known female celebrities.

But despite her meteoric rise to fame, it is what she did in the next few years—during the Second World War—that is truly extraordinary.

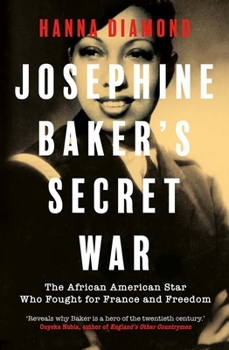

Josephine Baker’s Secret War: The African American Star Who Fought for France and Freedom (2025) by Hanna Diamond is an enlightening and thoroughly researched history of how one of the most famous celebrities of her time became a spy for the French Secret Services during World War II. It is also an important work, filling in a mysterious period of Baker’s life that helps explain her actions both before and after the war. Baker’s fame as a cabaret singer in the interwar years was well known. She also came to be known for her civil rights work in America and her humanitarian efforts globally in the 1950s and 60s. But drawing on contemporary sources, Diamond found that Baker was a valuable spy. She served as “our No. 1 contact in French Morocco” according to US wartime counter-intelligence officer Lt. Paul Jensen. Her support of the allied mission “at great risk to her own life” included helping pass along information that proved crucial at key moments of the conflict, such as after the allied landings in north Africa in 1942. Diamond’s new account helps explain the motivation for Baker’s involvement. We also learn how her actions shaped her post-war advocacy.

Baker’s decision to stay and fight for her adopted country, writes Jon Henley, “came from the huge debt she felt to France, which had made her a star—and it had its roots in the racism she grew up with.”

The writer Chloe Govan described Baker’s pre-war connection to the French in these words:

“She formed a special relationship with France due to its values of equality and freedom—quite unlike the ultra-conservative and religious atmosphere she had grown up in. For her, the skimpy costumes she now wore represented not shame and scandal but freedom from the oppressive culture which had persecuted her.

Meanwhile, her banana dance was an act of reclamation—taking back ownership of hurtful caricatures and reinventing them on her own terms. Once a tool of derision mocking her race, they could be reclaimed and redefined through costumed performances. The crowd implicitly understood—but sadly, this acceptance was unique to France.

On a 1928 tour, when she stepped outside the comfort zone of Paris and entered the largely Hitler-supporting territory of Vienna, she was met with boos and cries of ‘black devil!’. As indecency protests formed, Josephine was no longer a free woman, but a helplessly persecuted child all over again, crushed by racism. The church opposite even rang its bells during her concert to warn people they were ‘committing a sin’ by watching her perform.”

Baker had married and become a French citizen in the years before the war. So when she decided not to move back to America as the Nazi threat grew, she “stayed as a Frenchwoman, not as a Black American.” Diamond notes,

“Discrimination was behind her decision to stay in France. In Paris, she had distanced herself from the other African-American exiles. She wanted to be French and when the war came, unlike others who left France, she stayed to support her compatriots.”

Diamond carefully crafts three interlinking themes into Josephine Baker’s story. “The first is the theme of celebrity.” With her fame and easy-going manner, Baker learned to use her celebrity as a cover, enabling her “to play her part in the battle to free Europe from Nazi oppression.” It was relatively easy for Baker to move between countries as she entertained troops and met with local and national leaders. She became, notes Diamond, “a remarkably effective undercover intelligence agent for the Allies and for France.”

The second theme that weaves throughout the chapters is Baker’s growing “rediscovery” of her own African American identity. Much of this came from her contacts with American troops in North Africa, her base of operation for the first few years of the war. Baker’s personal growth led her to join the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, to the point that she had a speaking role during the famous 1963 March on Washington alongside the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Finally, Diamond explores Baker’s social fluidity—rare for anyone but rarer still for a Black woman—to “gain acceptance across different social groups and nationalities,” allowing her to play “an invaluable international role as a cultural facilitator and diplomatic intermediary.”

Diamond provides the reader with accounts of Baker’s growth as an undercover agent; how she learned spy craft from her handler and sometime lover, and the inventive ways she would hide messages in her bra or written with invisible ink on her music. It turns out she was a very good spy. “She proved expert enough at it to be awarded, after the war, the resistance medal and, belatedly, the Légion d’honneur with the military Croix de guerre.” Through Diamond’s writing we learn about Baker’s devotion to the Gaullists throughout the war and about her service as a second lieutenant propaganda officer of the auxiliary services of the Women’s Air Force. She easily slipped back into her role as a performer after the war. The French and all the Allies recognized her contributions, at least on a superficial level.

But we also learn of Baker’s blind spots. She could be a vocal advocate for racial minorities in the United States while at the same time, due to her “idealization of France,” keep largely quiet when the country’s north African colonies pushed for independence.

In 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron decided Baker should become the first Black woman to enter the Panthéon in Paris, the mausoleum for France’s “great men.” The French president’s reference of her wartime activities—which were a revelation to many—completely “transformed Baker’s legacy both in France and overseas.”

Diamond sums up Baker’s actions and legacy by noting that it is fitting that she attracted France’s highest national honor.

“Her wartime actions were driven more than anything by her conviction that France and its republican traditions had to be defended. France had offered her safety and opportunity, allowing her to thrive as an African American entertainer and to achieve a degree of success that would have been impossible in the context of America’s racial divisions. Her attachment to France was visceral and she embraced France completely. . . . After the war, Baker commented that ‘My life as a spy is the story of a Frenchwoman who loved her country.'”

Josephine Baker used her talents and her fame to fight for France and for freedom. So many, with so much more privilege, have done much less.

More to come . . .

DJB

Top images of Josephine Baker from A Mighty Girl

Pingback: Observations from . . . November 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: November 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...