Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” is an important reminder of why America rejected kings.

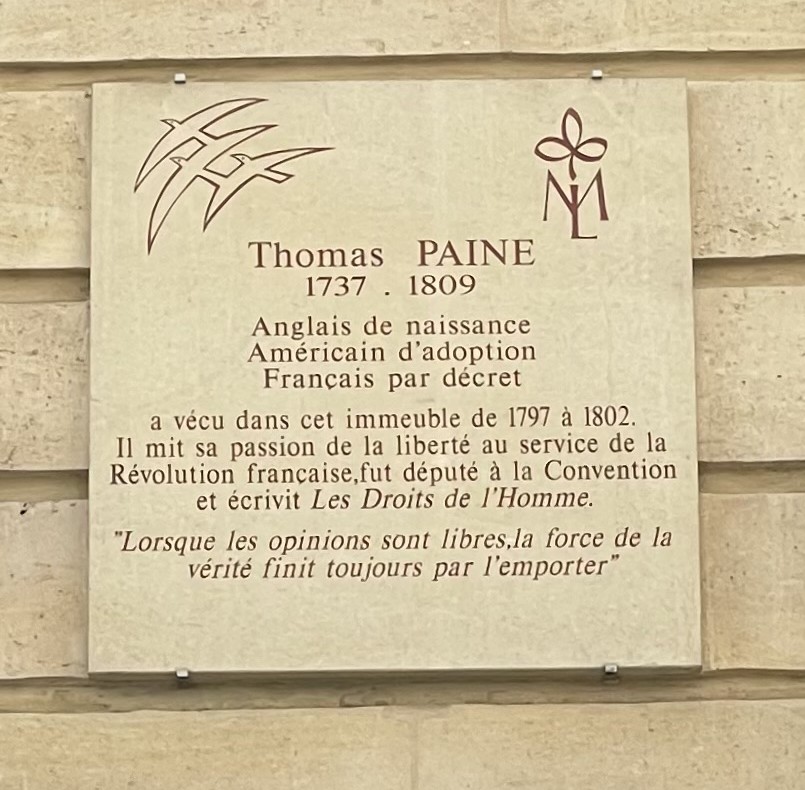

There was a confluence of events in recent weeks that led me to read—for the first time in years—one of the most important books in American history. While leaving a small restaurant in Paris in early October I looked back to see this plaque, only then discovering that we’d been in the building where Thomas Paine, the great American patriot, had lived during his time in the city.

Less than two weeks later, we were home for another reminder of the original fight against kings. Hearts and minds about where we currently stand—and what we stand for—as a country had begun to shift. Rebecca Solnit observed the difference in both words and actions of Americans, noting that something in the body politic changed over the last five weeks.

“It was manifested in the epic scale and fierce determination of the nationwide #nokings protests on October 18. The demonstrations and marches were in small towns and red counties as well as cities and blue states. But that was just a manifestation of the rejection of the cruelty and destructiveness of the Trump Administration and its nine months of mayhem.”

Finally, I watched the recent Ken Burns documentary The American Revolution where we heard the words of patriots, loyalists, Native Americans, enslaved men and women, kings, and future presidents all speaking to us from history. Two voices resonated most deeply with me: Abigail Adams and Thomas Paine. Adams wrote perceptive letters over the years to a wide circle of family and friends. Burns ends the documentary with her words about what the revolution and the ratification of the Constitution offered to Americans, if only we were wise enough to avail ourselves of the opportunity.

“. . .our Government daily acquires strength and stability. The union is complete . . . nothing hinders our being a very happy and prosperous people provided we have wisdom rightly to estimate our Blessings, and Hearts to improve them.”

Letter from Abigail Adams to Lucy Ludwell Paradise, 6 September 1790

Thomas Paine spoke more prophetically, his stirring words calling for the people of the United Colonies to become active citizens of what he was the first to characterize as the United States. As the series ended, I began to read Paine’s most famous book.

Common Sense (1776) by Thomas Paine, published just six months before the Declaration of Independence, has been called the most influential polemic in all of American history. It is a fiery call for his adopted countrymen to throw off the yoke of British rule, and especially to revolt against the crown. Common Sense provided the vision of independence that would move millions in that fateful year to change their hearts and minds away from their deference and loyalty to Britain and the throne. Americans had never heard such words. The pamphlet sold 100,000 copies in the first three months, and perhaps as many as 250,000 in the first six months after publication. There is, simply, no other publication as important to an era when Americans were beginning to think there was a different way forward than the one their London-based government insisted was proper, righteous, and inevitable.

Fast forward 250 years and we now have an administration and a political party that wants us to believe they are unstoppable, righteous, and on the side of liberty. But one only has to read the words of Thomas Paine—that “the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise”—to see the similarities between King George III and our would-be autocrats who want to build a garish ballroom on the rubble of the historic East Wing of the People’s House.

Reading Common Sense is a revelation. We are aware of Paine’s easy to remember lines of the “Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered” variety. But in reading the entire pamphlet, I came away with greater appreciation for his direct and harsh attacks on kings. For his “suggestions” of a way forward such as with the call for a “manifesto” that revealed itself six months later in the Declaration of Independence. For the brilliance of his argument that putting off the inevitable split from England would only lead to a less satisfactory long-term outcome for “the continent,” a term he favors for America. For his recognition that “the time hath found us” and that it is “not in numbers but in unity that our great strength lies.”

In his Age of Folly: America Abandons Its Democracy, author Lewis H. Lapham includes the essay The World in Time. When he turns to Paine, Lapham doesn’t find himself

“. . . in the presence of a marble portrait bust,” but meets instead a man “writing in what he knew to be ‘the undisguised language of the historical truth.’ To read Tom Paine is to encounter the high-minded philosophy of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment rendered in words simple enough to be readily understood.”

Instead of addressing the rich Paine “talks to ship chandlers and master mechanics, and in place of a learned treatise he substitutes the telling phrase and the memorable aphorism: ‘Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom must, like men, undergo the fatigues of supporting it.’”

This edition is paired with an essay first published in December of 1776. Paine’s famous opening to The American Crisis, written during the hardships of Valley Forge, resonates today as much as it did when Washington’s small army was fighting for its life at Trenton and Princeton.

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.”

I paired my reading of Common Sense with another work to stir the soul in these days of trouble.

Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations (2006) by Craig Nelson is an excellent biography of the man who though he was born in England, was truly a citizen of the Enlightenment world. Paine would write three of the bestsellers of the eighteenth century, topped only by the Bible. Common Sense cemented his reputation. Rights of Man helped shape the French Revolution and—although it would take more than a century—inspire constitutional reform in Great Britain and foreshadow Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Age of Reason, a forceful call against organized religion, finds Paine sticking to his Enlightenment and deist values even at the expense of his public reputation. Paine’s mind was clearly a force of nature, and Nelson characterizes him as “the Enlightenment Mercury who sparked political common cause between men who worked for a living and empowered aristocrats across all three nations.”

One of Nelson’s great accomplishments is to explain Enlightenment thinking and values in a way which places Paine and his work in a well-constructed context. Paine certainly has his flaws as a person, but he is more easily understood when placed within the value system that drove so many of the leading philosophers and political leaders of the late eighteenth century. Nelson’s other important accomplishment is to showcase Paine’s incredible relevance today.

As I have said on several occasions, as we struggle through constitutional crises and threats to democracy, we would do well to rediscover one of our most important founding fathers. Paine’s writing just might be the tonic to point us towards democracy, yet again.

More to come . . .

DJB

Top Image: Laurent Dabos. “Portrait of Thomas Paine.” National Portrait Gallery.

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . December 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: December 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Times that try men’s souls | MORE TO COME...