In honor of the 16th president’s birthday later this week: An intimate study of Abraham Lincoln’s powerful vision of democracy

We like to believe our troubles are unique. That our age is different. Yet so many of our current frustrations with democracy were encountered more than a century and a half ago by Abraham Lincoln.

According to historian David Reynolds, Lincoln has been the subject of more than 16,000 books. That’s around two a week, on average, since the end of the American Civil War. Historian Eric Foner notes that almost every possible Lincoln can be found in the historical literature,

“. . . including the moralist who hated slavery, the pragmatic politician driven solely by ambition, the tyrant who ran roughshod over the Constitution, and the indecisive leader buffeted by events he could not control. Conservatives, communists, civil rights activists, and segregationists have claimed him as their own. Esquire magazine once ran a list of ‘rules every man should know.’ Rule 115: ‘There is nothing that can be marketed that cannot be marketed better using the likeness of Honest Abe Lincoln.'”

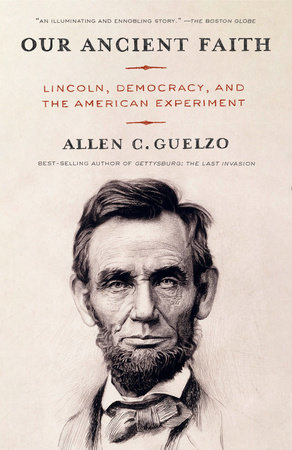

In a short, compelling work published just before the 2024 election, one of the Great Emancipator’s most distinguished biographers—one who probably never thought about how to market Honest Abe—looks at the ideas and beliefs about democracy that helped carry Lincoln, and the nation, through the horror of civil war.

We would do well to consider them again. In our time.

Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment (2024) by Allen Guelzo is written for those “who have despaired of the future or whose lives have been ruined by the failures of the present.” Lincoln came along in his time to rescue our democracy on its last gasp. His was an intervention “so unlooked for as to defy hope.” Guelzo, who is a lover of democracy “as only the descendant of immigrants can love it,” focuses on Lincoln’s principles with both the skill and passion of someone who yearns that “this last, best hope of earth may yet have a new birth of freedom.” This is a story that, as one reviewer notes, is for those short on hope and—just as important and just as troubling—perspective. Guelzo reminds us, as all good historians do, that while we live in difficult, uncertain times and have worries about our future, so it has nearly always been.

In nine chapters framed by an introduction on the disposition of democracy and an epilogue that asks what if Lincoln had survived Booth’s assassination attempt, Guelzo walks the reader through different aspects of our democratic system and how Lincoln was shaped, and then helped shape, those attributes and elements. Early on he reminds us that in tyrannies, governments rule; in liberal democracies, governments represent. People are judged competent to direct their own lives in democracies without the “paternal tyranny” of aristocrats, monarchs, and oligarchs. But Guelzo doesn’t shy away from democracy’s deficits. Assuming that the majority is always right and good and therefore has a license to rule is a fundamental weakness. But in his opening chapter he speaks to the tools by which democracies protect the balance between majority and minority rights: citizenship, elections, and forums for discussion (traditionally, in America, the newspaper and political party).

Even though Lincoln was born while Thomas Jefferson was still president and George III was still king, a new liberal economic world was already being born. In examining what Lincoln had to say about democracy in these fluid times, Guelzo notes that for Lincoln this was personal. He was a “poor man’s son” who was personally transformed by democracy and its reliance on laws and reason. Human liberty, he believed, was nourished best in a democracy because it relies on the consent of the governed. Lincoln was fond of pointing out that if slavery was such a good thing (as its apologists kept maintaining), why was it that no man ever sought the good for himself! He was also a believer that passion was at the root of ideological bullying, such as seen throughout the South, and he worked to dissuade northern Republicans from responding in kind.

Several of Guelzo’s chapters stand out, beginning with his examination of democratic culture: the laws and mores that underpinned America. Of the four mores that had particular force for Lincoln—property ownership, religious morality, toleration, and electioneering—he both lived within them and shaped them. Lincoln, Guelzo writes, had a “cagey relationship with American religion.” He never embraced his family’s Calvinism or anyone else’s religious beliefs. He could converse in the language of American church-goers, but “by the time he wrote his second inaugural address, Lincoln was prepared to turn that speech into something that walked at a tremendous distance from the religious cliches that permeated the inaugurals of previous presidents.” The chapter on civil liberties also opens up important insights into Lincoln’s character.

“[Lincoln] never used the term obedience to the law, but always reverence, seeming to regard that term higher and more comprehensive than the other . . . I remember very distinctly [wrote the reporter William H. Smith] that he spoke of this reverence for the law as the ‘palladium of our liberties, our shield, buckler and high tower.’ For all that we today laud Abraham Lincoln for his other virtues, it is this fundamental hesitation to quash law and democratic liberties which is the most important gift we inherit from him. As he was not a slave, so he was not a master.”

After working through chapters on democracy, race, and emancipation, Guelzo ends with a speculative chapter: “What If Lincoln Had Lived?” I am generally not a fan of these types of “what ifs” because they usually don’t acknowledge that the individual’s legacy is, in part, shaped by his or her early and sometimes tragic death. For me, Lincoln’s place in resetting democracy to rest upon the Declaration of Independence—best exemplified through the Gettysburg Address and the call to bring about a new birth of freedom—was strengthened and ensured because he, too, gave “the last full measure of devotion” at the very end of the conflict. Just like those who “gave their lives that that nation might live,” Lincoln also made the ultimate sacrifice and quickly belonged to the ages in a way that would have been impossible had he been forced to slog through four hard years of Reconstruction. To his credit, Guelzo handles this deftly and sensitively.

He makes the point that although Lincoln had skills superior to Andrew Johnson in almost every way, the results may not have been much more different even if he’d lived. And with this point, he brings Lincoln’s time and our own together, even making reference to the problems of the Supreme Court in the 19th century and our own day.

“Democracies tend to wait until a situation gets completely out of hand, and only then gather their full strength for a solution, and that puts them in danger from autocracies and dictators that can strike quickly and forcefully. Yet, remarkably, they possess a resilience which allows them to spring back from catastrophes in ways totalitarians have shown over and over again that they cannot.”

Guelzo ends this important work by speculating on the characteristics of a Lincolnian future in today’s world: a recovery of consent, an embrace of equality, a democracy in which citizen is the highest title it can bestow.

And to make sure we have fully understood his point, Guelzo concludes that, in a Lincolnian future, “there will be neither slaves, nor masters.”

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo of Lincoln Memorial from Pixabay.

Pingback: Observations from . . . February 2026 | MORE TO COME...