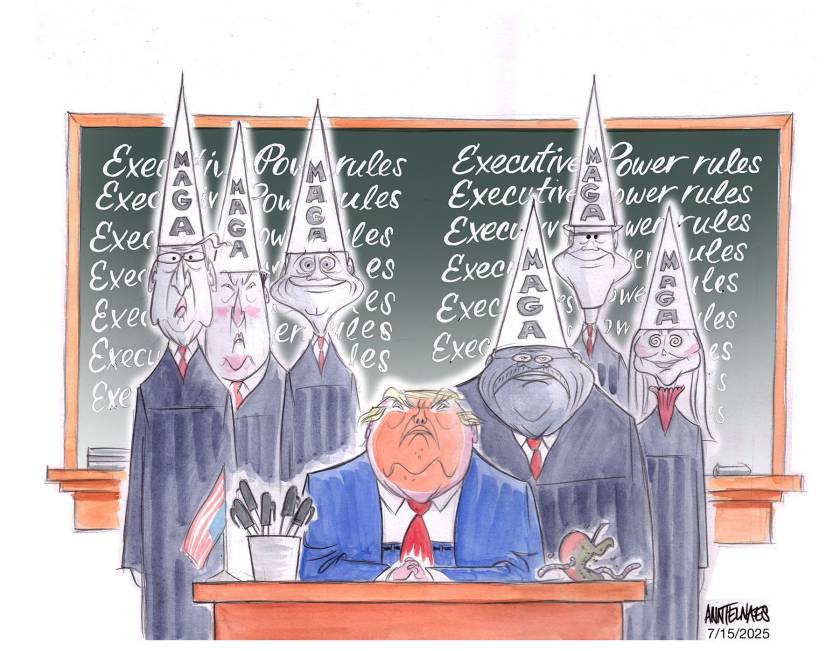

If it is a day that ends in Y, there is a good chance that the U.S. Supreme Court will release another decision disconnected to the rule of law and the Constitution. It happened again on Monday with a decision (6-3 and unsigned) allowing the dismantling of the Department of Education. Professor Steve Vladeck suggested that “comparing Monday’s unexplained grant of emergency relief in the Department of Education downsizing case to how the justices handled President Biden’s student loan program is … telling.” Journalist Marcy Wheeler made the impact more understandable for the general public, writing that “John Roberts just gave a billionaire wrestling promoter accused of letting an employee sexually exploit boys sanction to start destroying local school programs.”

Justice Sotomayor, in her strong 19-page dissent, wrote that “it is the Judiciary’s duty to check … lawlessness, not expedite it.”

A constitutional law scholar and court watcher recently suggested that the citizens of the U.S. need to adjust how we view the nation’s top court. “We often think of law as something that is objective and determinant, where there are right answers,” she said.

But as Leah Litman told writer Sharon Morioka, the “aha” moment that this was not the way our current Supreme Court approaches the law “came a few seasons ago when she was reading a Supreme Court decision and decided that it was influenced by the justices’ own biases toward the issue.”

The result of that revelation was a book which makes another strong case about how seriously off track this court has driven the country.

Lawless: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories, and Bad Vibes (2025) by Leah Litman describes in fresh and accessible language how the combination of the court’s power and a poor understanding of its work by the public makes it a dangerous entity in today’s America. While lower courts concluded that “the Fourteenth Amendment barred Trump from holding office under the provision that disqualifies people who, after having taken an oath to the United States, ‘engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same'” all of the Supreme Court’s January 6-related interventions “cleared the way for Trump to run for president again and to ultimately be reelected.” If we aren’t paying attention or we think we misunderstood the decision because it couldn’t possibly be that ridiculous, then the Court can get away with what is obviously ridiculous. However, if you are among those convinced that Republicans, and especially white male Republicans, are treated unfairly by an increasingly diverse society that no longer shares their views, then the move to make decisions based on conservative grievance, fringe theories, and bad vibes is an easy step to take.

“Conservative grievance” as Litman describes it, is the idea held by some of the justices that “conservatives are the victims” of a society that doesn’t share their views. “Fringe theories” suggests that the court is drawing on views held by a minority of the country. And “vibes” are the most subjective of all; they’re your innermost feelings. “By suggesting the court is drawing on vibes rather than law,” Litman notes, “it’s meant to suggest that what they are doing is imparting more of their own views into the law that governs all of us.”

Lawless is similar to Adam Cohen’s 2020 book Supreme Inequality. Both look at the longer view and their arguments are very serious. Unlike Cohen’s important work, however, Litman’s writing “is far from dry, with humor woven throughout the book.” Some of it doesn’t work for me. Using LOL as an aside seems more appropriate for an online newsletter. However, Litman is writing for a broader and younger audience, so I do appreciate her taking the justices to task with humor. For instance, she notes that Samuel Alito (a frequent and sometimes too-easy target) made excuses for the upside down American flag associated with the Stop the Steal movement flying at his house a few days after January 6th.

“But fear not, America—Justice Alito insisted he ‘had no involvement in the flying of the flag.'”

“Alito said it was his wife’s doing: Mrs. Alito is apparently ‘fond of flying flags’ and ‘has the legal right to use the[ir] property as she sees fit.’ (Sam Alito, the author of the 2022 opinion overturning Roe v. Wade and women’s right to choose, thinks that [some] women can have [some] rights!)”

Litman looks at how the theory of originalism is used to advance ideological and political agendas. She makes it clear that Senator Mitch McConnell, perhaps better than anyone, understood that appointing the right people in concert with the Federalist Society was essential to furthering Republicans’ political agendas. She provides background on how discredited candidates such as Brent Kavanaugh made it to the Supreme Court and then were deeply involved in questionable (some might say nefarious) decisions, such as plotting the precise timing of how the future of abortion rights would play out to help game the politics of the moment.

In five chapters, Litman dives deeply into the Dobbs anti-abortion decision overturning a fifty-year right to choose, and the ominous implications for other rights for women (a “jurisprudence of masculinity”); the attempts to undermine the Obergefell decision permitting same-sex marriages; voting rights (a particular issue for Chief Justice Roberts throughout his career); bolstering minority rule (especially for the very rich); and the Court’s attack on government itself.

Republican justices “have had more than a few things to say about power and who gets to have it. (Republicans; it’s always Republicans.) Telling democratically elected legislatures they cannot enact laws guaranteeing equal treatment for historically marginalized groups is one thing. But it is far from the only thing,” maintains Litman. And she brings the receipts.

Justice Elena Kagan succinctly spelled out so many of the problems with this current court in her 2023 dissent to Biden v. Nebraska:

“…the Court, by deciding this case, exercises authority it does not have. It violates the Constitution.”

This involved a decision which rewrote a federal law which explicitly authorized the loan forgiveness program and relied on a fake legal doctrine known as “major questions” which has no basis in any law or any provision of the Constitution.

Litman reminds us of what we need to do. The world “is not going to get better” simply because we want it to.

“We have the court we have because there was a movement that fought for that court. If you want to change the court, you need to develop a long-term strategy. That’s not something that’s going to happen overnight, but it is something that can happen if you educate yourself, stay organized, stay invested, vote, and do all of the things that are just part of being an informed citizen.”

None of the stories in Litman’s book were pre-ordained, and she reminds her readers that neither is what happens next. Rebecca Solnit has written on the growing size of the coalition of those impacted by the right wing’s overreach and how “every cruel and destructive action by the Trump Administration is a recruiting opportunity for the opposition.”

There are a number of steps Litman outlines for those who care about democracy.

- Make the court’s behavior part of public discourse. “The justices’ legal reasoning isn’t serious; neither is their behavior. But the consequences for the country are.”

- We have to call out Chief Justice Roberts and the conservative supermajority who have unilaterally blown up the legitimacy of the Court. We can make it clear that Roger Taney no longer heads up the list as the worst Chief Justice of all time.

- Take every election, especially the local ones, seriously. Vote.

- Have a sense of urgency as well as a long term commitment.

- Ensure that the perfect doesn’t become the enemy of progress.

- Court reform is important: both term limits and court expansion.

- Ensure more congressional control over the courts.

- Remove the Court’s jurisdiction (i.e., power) to decide certain questions, such as limiting their ability to strike down laws ensuring everyone has a say in elections.

- Acknowledge that the court is political.

Those who care about our democracy will have to push (and push for years . . . remember that we have to build a movement for major change) for these steps and more. But we cannot, she reminds us, let one (really bad) Court kill our democracy. Litman ends this astute assessment of our condition with:

“They’ve stolen a Court and they are practically daring anyone to challenge them. It’s time to call their bluff.”

Knowing the past suggests ways forward for our future

Many other historians, law professors, and journalists have written about this work to cement inequality into American life. I’ve covered some of them in these MTC posts:

- The capacity for change (2025)—Jon Grinspan demonstrates how we have seen both extreme ugliness and bold reform through the years when it comes to our democracy.

- How to live—and think—through the challenges of our era of moral cynicism (2025)—A compelling biography of Hannah Arendt that is also a primer for how to think if we want to be free.

- Rewriting the past to control the future (2025)—Jason Stanley’s Erasing History makes the case that those who fight for the past can save the future.

- Systemic change only occurs after acknowledging a systemic problem (2025)—Tech leaders, writes Marietje Schaake, do not have the mandate or the ethics necessary to govern so much of our societies.

- Legitimacy, once lost, is hard to reclaim (2023)—Adam Cohen’s devastating and damning argument against the Republican party’s fifty-year plan to circumvent the Constitution, overturn the gains of the New Deal and Civil Rights eras, and cement inequality into American law and life.

- The continuing fight for the soul of America (2022)—Historian Heather Cox Richardson’s searing, provocative, and masterful How the South Won the Civil War reminds us that the struggle to provide equal opportunity for all is never finished.

- Belief in a common purpose (2021)—The New Deal mattered in 1933, writes historian Eric Rauchway, because “it gave Americans permission to believe in a common purpose that was not war.” Although conservatives have fought against the ideals of the New Deal, neither before nor since have Americans so rallied around an essentially peaceable form of patriotism.

- The abandonment of democracy (2020)—I was reading Nancy MacLean’s compelling Democracy in Chains at the end of 2020 while watching the attempted coup that took the attempt by the billionaire-backed radical right to undo democratic governance to its logical conclusion. Utterly chilling.

- Towards a more perfect union (2020)—Historian Eric Foner’s work on the “second founding” of the country examines why “key issues confronting American society today are in some ways Reconstruction questions.”

- History is a teacher (2019)—Historian Joanne B. Freeman’s The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War is the riveting tale of mortal threats, canings, flipped desks, and all-out slugfests…and that’s just on the floor of Congress! Only when we stand up to those who would divide us and push for a true reckoning will we break through the polarization.

- Telling the full story (2017)—The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by historian Edward E. Baptist demonstrates that slavery was not some pre-modern institution on the verge of extinction but was, instead, essential to American development and, indeed, “to the violent construction of the capitalist world in which we live.”

The fight for democracy and justice never ends.

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo of Supreme Court building from Pixabay.

Pingback: Observations from . . . July 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: From the bookshelf: July 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The year in books: 2025 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: A moment like this | MORE TO COME...