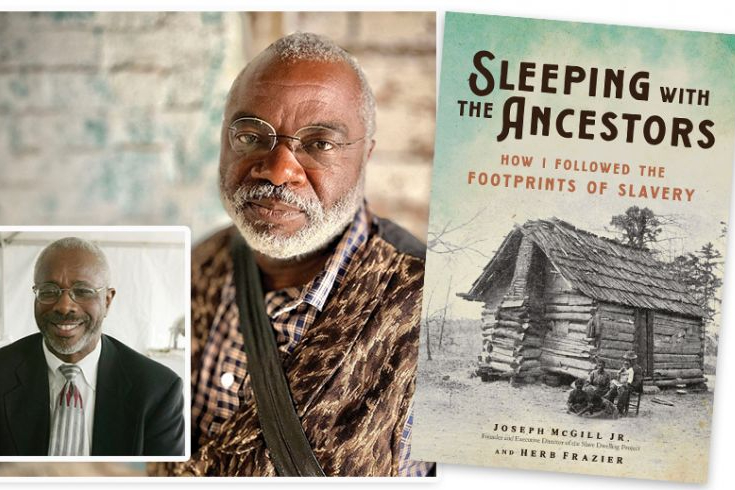

UPDATE: Congratulations to Joe for the New York Times review of his book!

Historic preservation has, from its very beginnings, been tailored to serve present-day purposes and shape how the future views the past. As histories of the movement show, the selection of what we save changes as we come to understand the importance of less celebrated histories, the contributions of marginalized communities, and the value of wider perspectives.

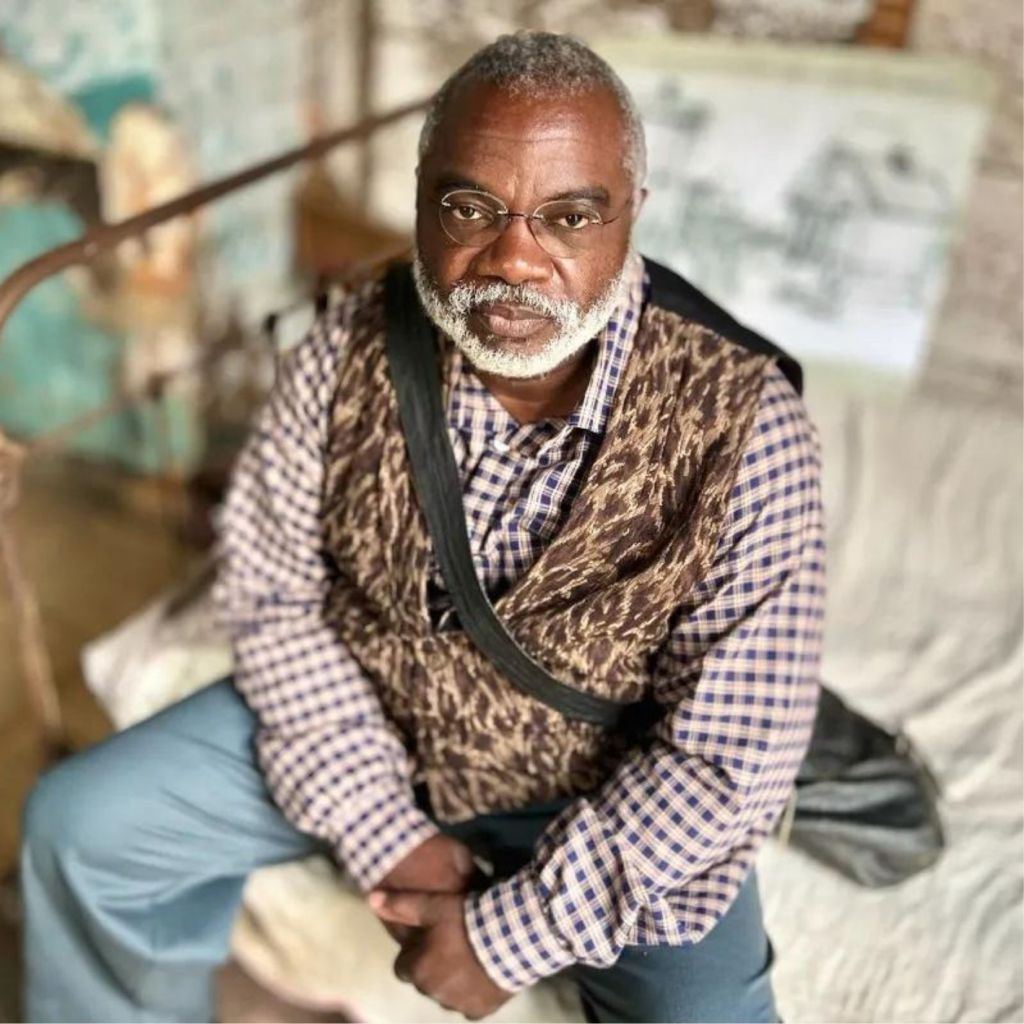

Sleeping With the Ancestors: How I Followed the Footprints of Slavery (2023) by Joseph McGill, Jr. and Herb Frazier is a compelling work about a crusading effort to draw attention to the preservation of dwellings where enslaved people lived, worked, and raised their families. A former colleague of mine at the National Trust who founded and leads The Slave Dwelling Project, Joe and his co-author Herb Frazier have compiled a captivating account of his years working to “change the narrative, one slave dwelling at a time.” In it, the authors recount the broadening of a modest regional effort into a national force. Joe graciously agreed to chat with me about the book and his work.

DJB: Joe, were there particular places that led you to begin sleeping in slave dwellings and that helped shape the project?

JM: Several factors came together in making this decision. While in college I accepted a summer job as a park ranger at Fort Sumter National Monument. In undertaking research on the Civil War, I came across flaws in the history that I was taught: the indigenous people were not the enemy, enslaved people were not happy with their lot in life, and the people enslaving them were not benevolent.

As a park ranger, I would interact with Confederate Civil War reenactors whose knowledge was of the Lost Cause variety. My ongoing research and the 1989 movie Glory inspired me to become a reenactor of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry to honor the 200,000 Black men who served for the Union during the Civil War. Participating in reenactments where we camped overnight provided me with access to historic sites after hours. That was another step in the process.

Later I became director of history and culture at the Historic Landmark District of Penn Center on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, where the buildings pertained to the history of African Americans. As a program officer for the National Trust, I became even more attuned to the knowledge of preserving buildings while working to convince the public that slave dwellings matter.

My epiphany for loving historic spaces predates my professional career. While in the Air Force I visited the home in Amsterdam where Anne Frank hid from the Germans during World War II. The physical space made my limited knowledge of Anne Frank come alive, just as the physical space of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, brought tears and a desire for militancy.

Where were some of the most surprising places you found that housed slaves?

In my history books and Hollywood, the happy enslaved people and their benevolent enslavers lived on plantations. Slave cabins are on plantations, so I initially called my work The Slave Cabin Project. But on a sleepover at Old Alabama Town I immersed myself in what urban slavery was like. Most importantly, I stayed in a two story, four compartment, brick building. This was certainly not a slave cabin.

What was clear from the project’s onset was that the word slave was essential for the name of the project but changing “cabin” to “dwelling” made the project more inclusive.

What was most devasting to learn was that slavery was not just a southern thing. After the American Revolution, northern states abolished slavery legislatively yet they remained complicit because the banks, insurance companies, slave ships, and factories adding value to cotton were all north of the Mason Dixon line.

My first northern sleepover in a slave dwelling was Cliveden in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At Fort Snelling in St Paul, Minnesota, I slept in the place where Dred Scott slept. It is those places where I’ve stayed in states like Wisconsin, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Massachusetts and Rhode Island that are most rewarding to me.

What places have been resistant to the idea of a sleepover, and why?

Several institutions of higher learning owe their existence to the institution of slavery. Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, Virginia, was my first sleepover on a college campus, and I’ve had many since. While Clemson University and the University of Virginia are on the list of the places stayed, some obvious ones missing from the list are two in South Carolina — the University of South Carolina and Francis Marion University — as well as The University of Alabama.

It took me five years to get a sleepover at Mt. Vernon, as it was not their intent to interpret George Washington as one of 12 slave-owning presidents. Natchez, Mississippi, was also a very tough nut to crack because of its love for celebrating hoop skirts and mint juleps at their annual pilgrimage. The local garden club has control of how history is interpreted in Natchez.

Many sites do not want to engage for fear of reparations. Despite that fact there are great examples of places that are working diligently with the descendant communities including James Madison’s Montpelier in Virginia; Middleton Plantation and Historic Brattonsville in South Carolina; and Sommerset Plantation and Stagville in North Carolina.

How has the Slave Dwelling Project changed the way historic sites, museums, and preservation organizations present the narrative around slavery?

Ten-to-twenty years ago, one would be hard pressed to encounter a historic site that interpreted slavery in a researched and respectful manner. Now historic sites are ridiculed if they don’t include the narratives of the people once enslaved at their sites. In my thirteen years of leading the Slave Dwelling Project, I’ve witnessed and influenced the changing of the narrative.

Some sites that said no to my request initially have since allowed me to conduct sleepovers, once I had established a track record. Sites are now calling me, and more are engaging with their descendant communities. The words “enslaved” and “enslaver” are now permanently embedded in the lexicon. We are working on using the term “freedom seeker” instead of “run away.” Some encourage using the term “forced labor camp” instead of “plantation,” but I’m not there yet.

By that same token, some are still afraid of the word plantation. That is why one can visit Monticello, Montpelier, the Hermitage, Mount Vernon, Drayton Hall, Middleton Place all in an effort to minimize what those places really are. They are all plantations.

Joe, what books and authors influenced your work that you would recommend for readers who want to know more?

I consider the book Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery by John Michael Vlach to be my bible. The title of the book is bold and appealing to me.

Slaves in the Family where Edward Ball researched and published the findings on his slave owning ancestors is also a good read.

They are hard reads, but the Slave Narratives are necessary for anyone doing serious research about slavery in the United States. One must be careful in using them because most of the interviewers were white and this was during a period in history when Blacks were more intimidated. Despite that reality, Slave Narratives is still a good resource for researching chattel slavery.

Thank you, Joe.

Thank you for the opportunity.

More to come…

DJB

Pingback: Observations from . . . July 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The books I read in July 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Lovely to read this. I had the privilege of sharing a night with Joe and a colleague in a cottage that had housed enslaved people at the University of Virginia. This was part of the 2017 symposium on institutions studying slavery. Such a powerful, instructive, and humbling experience.

Emily, so glad to hear from you and to hear of your experience with Joe and the Slave Dwelling Project. Others who have participated have noted similar reactions. I’m glad Joe was willing to chat with me about his work. All the best to you, DJB

Pingback: Observations from . . . September 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Talking with writers | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Best of the MTC newsletter: 2023 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2023 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Pull up a chair and let’s talk | MORE TO COME...