Americans are confused.

We think of ourselves as a nation that makes stuff. In the past thirty years 63,000 factories have shuttered.

We think of ourselves as a free nation. We, Americans of all colors, are the most incarcerated people on the planet.

We are home to the most innovative healthcare system on the planet. High healthcare costs have been our nation’s leading cause of bankruptcy for decades.

We are home to many of the world’s greatest universities. Millions upon millions of our students and graduates are in massive debt.

The life expectancy for Black men remains low, “suppressed by sky-high homicide rates,” while the life expectancy for White men has been “declining for years” driven by suicide rates that are even “higher than the homicide rates for Black men and boys.”

It can be hard to remain optimistic about the future when we consider the harsh reality of life in 21st century America. Yet there are strong voices, speaking from a lifetime of activism, who tell us that having faith that we can hand over a better nation to our children is the “only path to national survival, let alone true greatness.”

They believe “we can rise up together to demand freedom on behalf of all our children.

But first we have to start listening to each other.”

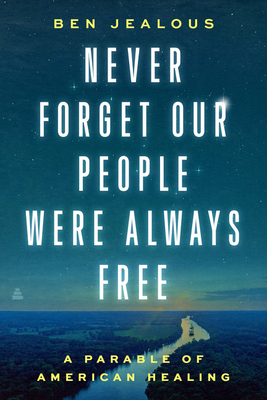

Never Forget Our People Were Always Free: A Parable of American Healing (2023) by Ben Jealous is a work of pragmatic and enduring optimism in a sea of national malaise. President of People for the American Way, former president of the NAACP, civil rights leader, scholar, and former journalist, Jealous writes from a lifetime of reaching out to others and listening to what they have to say. In this engaging memoir, Jealous uses a series of more than 20 stories from his life — modern-day parables — to make the point that we must truthfully and fully address the tensions that have been building up throughout this century if we are to survive.

Jealous, the son of a White father and a Black mother, understands that we are all connected in ways both natural and spiritual. Early in the book he tells the story of meeting a man and woman from Los Gatos — the husband grew up in Minnesota and the wife in Virginia — at a retreat weekend in California for people who played important roles in their community. It turns out both Jealous and the woman of the other couple are from Petersburg. When he hears that “Bland” is her maiden name, he takes a big gulp of his drink and then says to the man, “I don’t know how to say this. I think your wife’s family used to own my mama’s family.” And the woman relates that she always knew she had Black family because “Mammy raised me until I was twelve” and “I could tell she was related.” Who is my family? is a familiar theme throughout the book. It turns out we’re all — in many ways — cousins.

Jealous uncovers and considers other revelations that would surprise many readers. Historians have documented that race, as we know it, was not a factor in the first century of the American experiment. Later, the civil rights movement helped Blacks get what they fought for but in the process they often lost what they had. The “legacy of race and racism has led our nation to equate poverty, addiction, and handgun deaths with Black people” and to ignore “even larger numbers of suffering White people and rendered uniting every one of those impacted communities all but impossible.”

Each of those narratives upends conventional wisdom in much of America.

Jealous finds friends and allies in unlikely places: Mississippi, Arkansas, and — that whitest of all states — Maine. “Race relations in America began with shared struggle, not mutually assured destruction.” We need to get back to working together for a better future.

Throughout this hopeful book, Jealous describes ways in which conversations, shared work, and thoughtful listening can lead to people striving towards freedom together. He gives specific examples that readers can relate to in their own lives. He has specific policy prescriptions, such as changing California law so that prisons no longer receive 50 percent more funds that state universities.

Jealous writes that he has long been indebted to General Colin Powell, who once told him, “Ben, it’s easy to recognize what you disagree with people on. What’s more urgent and important in any democracy is to spend your energy figuring out what’s the one thing that you can agree on with a political foe. Figure that out and you can get a lot done.”

As he does throughout, Jealous in the end calls on the wisdom of his grandmother, who died at 105 as he was finishing this book. He once confronted this woman — who had spent a lifetime in the struggle for civil rights, human rights — to ask how she could be so lighthearted and positive. Didn’t she know how much was wrong in the world?

“Baby it’s true. Pessimists are right more often, but optimists win more often. In this life, you have to decide what’s more important to you. As for me” — she smiled — “I’ll take winning.”

More to come . . .

DJB

Photo by Jackson Hendry on Unsplash

Pingback: From the bookshelf: February 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: Observations from . . . March 2024 | MORE TO COME...

Pingback: The 2024 year-end reading list | MORE TO COME...